Maybe if I had seen Gus van Sant's Elephant I would be moaning about this movie being derivative to the point of being a straight copy of it. I didn't, so am not in a position to make any comment. I am glad, however, that I did see 2:37. It was a pretty gruelling watch in a couple of places, where the director was pretty confrontational in the way he handled the scenes but, after having them circle around in my head for a couple of days, I think they were important to be shown the way they were. I'll say more about these later, but can say more general things to defer the spoilers. 2:37 is the time at which the movie starts - it doesn't take a genius to add together a locked school bathroom door, the sound of someone falling to the floor and blood seeping out under the door to arrive at the conclusion that the movie starts with a suicide. The movie ends with us actually seeing the suicide happen - not a pretty sight: there has been a long, slow take as the person in question walks to the bathroom, locks the door, and then draws blood. Apparently, this piece takes over five minutes.

The particular time has been chosen because it is the time at which a friend of the film maker took her own life (well, maybe: apparently there has been a big bunfight across the pond about the accuracy of this claim), an event which initially prompted him to try the same. Luckily, it didn't work, and he decided to make what he claims is a life affirming work. I'd say that he'd been reading too much Beckett, but I doubt that he's heard of him: the interview I read revealed a startling lack of cultural knowledge. At best, I'd say that it might discourage some from suicide. It might make others think there is no other way out, which is why it has an R18 rating in Australia.

So, the movie starts with all the signs of a suicide, and an anxious Melody trying to get in to the bathroom. It is clear she thinks she knows who it is, the teacher she calls to help also thinks he knows who it is: as the film unravels, it becomes clear that they both have a different person in mind and are both wrong. The idea is that we play along and try to work out who it might be. The form of the film is to go back to the beginning of the day and cycle round through half a dozen school kids, showing a piece of their day: each links to the next. So, we might have an episode in which we see Melody, for example, talking to someone. We'll then see the next person hearing that conversation as they move into their own episode. One critic sees the technique as creating some sort of prison, but I'd say that it is more important to see it in terms of a closed loop.

For each, there is a kind of segment of an interview, shot in black and white to create an atmosphere of cinema verité. As we go round, another layer is revealed: so Melody first time round loves animals and kids, wants perhaps to be a primary school teacher. By about the third go round, she has no idea.

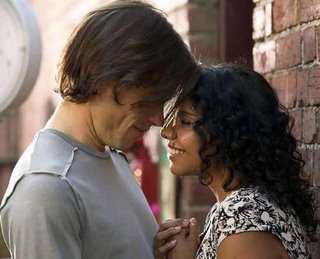

I'm picking on Melody because, insofar as this film has a central character, she's it. She was also my favourite character. On the first go round, my pick was that it was her brother, Marcus, who had committed suicide: he seemed highly strung and "artistic". Sean was the gay guy, but he was out about it, although a bit pissed that it got him into trouble. Uneven Steven was the fellow who had one leg shorter than the other and one urethra more than normal, with no control over the second one - with results which are embarrassing enough at the best of times, and a high school certainly ain’t that. Then there was the guy I hoped first time round would be the victim, Luke, because he was such a tosser (literally, as it happens) and finally, Sarah, the nice girl who just wanted to settle down and get married (to Luke, whose only conversational ability with her seemed to be "hey, babe") and dares anyone to have a problem with that.

By the time we'd finished our circuits of these characters, my attitude had changed completely: I hoped it would be Marcus who was in the bathroom. Logically, I knew it couldn't be Melody, as we were outside with her, looking at the blood, but she seemed to have most reason to be the one inside the bathroom. Of course, we have to make allowances for the way that problems appear so magnified when you're young and in a place where there's always going to be someone to make things worse for you. So, maybe if I'd wet my pants twice in one day, been chucked out of class by the teacher, been laughed at and then punched in the head by the tosser, that would send me over the edge too.

So, I found this quite a challenging movie to watch, for a couple of reasons: I want to talk about those reasons, but in doing so, I'll be giving spoilers, so look away now.

As I said, Melody had most reason to want to die: she finds out today that she's pregnant, and word is out all round the school. At the moment, Luke is getting the credit for being the father, but its only a matter of time before the truth is known: that she was raped. Not only was she raped, but she was raped in her own bed, by her own brother. Now here's the controversy: the director had us watch pretty much the whole thing - I won't go into details, but the camera is there as its happening, and it took quite some time. For many, as soon as they started to see this, they'd see how revolting it is. The thing is, that we see so much violence these days, that for some it takes longer - I know that when I was watching, it took a while, basically the whole scene, for the full horror of what was happening to hit me.

The one reservation I continue to have is that the camera at one point seemed to basically cop a peek, not for the first time in the movie; there was an earlier discomforting shot where we watch Melody get dressed. Maybe he was trying to make a comment on voyeurism, make us somehow complicit in what was happening, I just don't know.

The other spoiler, about who was in the bathroom, is where my comment about the filming technique creating a closed loop comes in. We're all so concerned about the dramas of the characters, and seeing their reasons for not wanting to go on living, that it doesn't necessarily occur to us that it might not be any of them. Certainly, there were at least two of the characters to whom this nice girl had been kind but who had been so self involved that they'd not given her the time of day. There may have been more: when it became obvious who was about to kill herself, I was struggling to work out her place within the movie. But I really can't see the movie, as has been claimed by some, as providing the simplistic moral that we should be nicer to each other, because we have Melody taking the last word, saying of the suicide, "she's the lucky one".