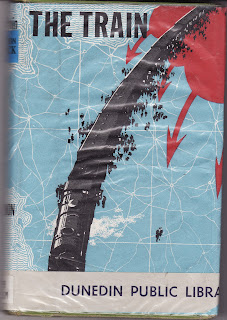

The Train, by Georges Simenon

I expected more drama in this wee book than it delivered. Marcel has a nice life: a wife, daughter, house self-employment in a business he enjoys. He lives his life according to a timetable established according to "habits rather than obligations". This life is disrupted by news that the Germans are about to invade; while they are fortunate enough to evacuate, Marcel is separated from his family on the train which is taking them to safety. A "young brunette in a black dress covered with dust", "pale-faced and sad looking" gets into the same waggon as Marcel and huddles in a corner. This is Anna. As the train starts to move, Marcel muses on the break: it is as if the town in which he has lived had lost its reality. He is a sickly man, lucky to be married and he knows it, yet he gives no thought to his wife and family: this carriage has become his reality. Simenon does a good job of presenting life in it.

Marcel's family are in the same train for a while; when it is made into two trains, he is not at all concerned that his family is heading in a different direction but finds himself in a bit of a pickle. He sees messages of sympathy in Anna's eyes and is unwilling to show her he does not care. He and Anna eventually join forces, saying hardly anything to each other but "as if by common consent", staying together for the duration of the train journey. On their first night, Anna draws him to her, on top of her, both "silent as snakes". This is a pretty new experience for poor old Marcel:

I came close to talking incoherently, saying thank you, telling of my happiness... I should have liked to express all at once my affection for this woman ... who was a human being, who in my eyes was becoming the human being... For the first time in my life I had said I love you like that, from the depths of my heart.

Eventually they're off the train and put in a camp, where Marcel claims Anna to be his wife so they can be together. She thanks him and asks what would have happened had they not let her in: "I'd have gone with you" and it didn't matter where.

So the basic thing is that he is living with Anna, feeling more for her than anyone in his life, including for his wife, in a state of "happiness which bore the same relation to everyday happiness as the sound produced by passing a violin bow across the wrong side of the bridge bears to the normal sound of a violin. It was sharp and exquisite, and deliciously painful."