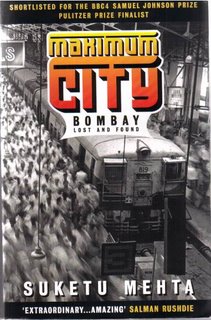

Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found by Suketu Mehta

I have only been to Bombay (or Mumbai, it depends who you talk to) for a couple of days but I think that no matter how long I might stay in this city, I would never get access to the kind of stories told in this book. Mind you, I'm not sure I'd want to, as he got himself into some rather dubious positions. His stated aim is to "follow eveything that made me curious as a child: cops, gangsters, painted women, movie stars, people who give up the world." He acheives this: the book breaks down into appropriate sections, except that such is the all-pervading influence of gangsters, there is an element of leakage between sections.

I have only been to Bombay (or Mumbai, it depends who you talk to) for a couple of days but I think that no matter how long I might stay in this city, I would never get access to the kind of stories told in this book. Mind you, I'm not sure I'd want to, as he got himself into some rather dubious positions. His stated aim is to "follow eveything that made me curious as a child: cops, gangsters, painted women, movie stars, people who give up the world." He acheives this: the book breaks down into appropriate sections, except that such is the all-pervading influence of gangsters, there is an element of leakage between sections.Mehta spent some of his childhood in Bombay, before leaving the country for 21 years in 1977. He has come back, partly so that his own children can gain an understanding of their roots but also because the place has always had a tight claim on his heart while away. So the book is not strictly travel writing: there are recollections of his childhood, stories of his attempts to settle in to what he dubs "the city of no" as he finds it very difficult to obtain the things he had learned to take for granted in New York - accomodation, electricity, telephone and so on. What there is not is any story about his family once they hit Bombay: he says that to protect them, he has to keep his distance from them, but there is a suspicion that he relishes the freedoms that their absence gives him.

Roughly half this six hundred page book is devoted to the power structure he encounters in Bombay. It soon becomes clear that it is not the police, the courts, the rule of law which has control here. Instead, it is the gangs - there are two main gangs split along religious lines, the Marathi nationalist Shiv Sena ("Army of Shiva") run by Bal Thackery and the Muslim Dawood Ibrahim gang. The former is very much the stronger, and had initially run in parallel to the municipal government, providing social services to its constituency, but has now reached the point that it has political power at city, state and national levels. Their powerbase is in the Marathi "sons of the soil"; in addition to being opposed to the Muslims but to those who are better off than them who, in turn, are "aghast" that this "race of clerks" won't stay in its place.

Mehta does not dwell on the ideological differences between the gangs: his focus is on their power and with the underworld in which they operate, acknowledging at one point his own growing fascination and exhileration with the dark and dangerous nature of this life. One of his early questions is "what does a man look like when he is on fire?" He spends a fair amount of time getting acquainted with the kind of people who know the answer to this question - hitmen from both of the gangs, a very highly placed policeman (who appears to be the one non-corruptible policeman in all of Bombay) and the leaders of both major gangs. He points the finger at Thackeray in particular, saying that he's a "man of monstrous ego", somewhere between Pat Buchanan and Saddam Hussein, someone (after talking to him for a while) of whom "I began to entertain the suspicion that he was not all there ... was a tired aging fascist". This was when he began to rave about the rat problem in Bombay and the need to ban Valentines Day, hardly the most major of that city's problems. He thinks small, which Mehta attributes to never having read a book in his life and his tastes for Bollywood movies and cartoons.

In particular, Thackeray is the man who has done more than anyone else to destroy Bombay. One way in which it has clearly broken down is the absence of any legal form of law and order: even the best of the police use the technique of an "encounter", in which thugs are simply eliminated. without any sort of due process. The courts are portrayed as completely unable to deal with the situation - not because of ineptitude, but because of intimidation and lack of resources. If you want "justice" in this city, you have it administered by the gangs. Even judges have been known to seek this assistance (or have it forced upon them). One odd consequence is that Bombay has become a comparatively safe city, with street crime quite rare; when the gangs can shake down a judge or a movie producer for a few lakh, I guess mugging becomes unnecessary.

The second half of the book takes up his interest in "painted women, film stars and people who give up the world". With the first of these, we are in the world of the "bar-line" girl, where there is a curious sort of innocence. A bar-line dancer is the sort of girl the gangsters from his first section are likely to go for. They work in beer halls, dance halls: "fully clothed young girls dance on an extravagantly decorated stage to recorded Hindi film music, and men come to watch, shower money over their heads and fall in love". The whole idea is to make the client fall in love and to make him think she is in love.

This is far more the courtesan than the straight out prostitute; they are women upon whom men project all their desires and with whom men do indeed fall in love, undertaking a perverse sort of courtship ritual. The women involved have a tightrope to walk: those who are any good are unlikely to have just the one suitor, so they have to treat each of their men as "special", as dancing just for him. Fine if only one of their men is in of a night, but things get tricky when there are more than one - they get the same sort of jealousy any man might get at the thought of losing, and respond, either with more extravagant gifts and promises or more extravagant violence. For the girls, it is a matter of stringing each along, taking vast amounts of money in the process, until eventually they have to provide sex. This is deferred as long as possible, however: the girls recognise that that will normally be the end of things.

Mehta spends a lot of time with two of these girls, one he calls Monalisa and another, Honey, who is actually a guy who successfully passes as a woman, but who is terribly conflicted over which role is most important to him/her, as Honey is also married and desperate to have a child. He meets both through a particular club he calls Sapphire, a club which is at the top of the game:

Over time, I started liking Sapphire. I liked the happiness there. Here were people who came after a hard day in a brutal city, and there was music they liked, and booze, and lights, and pretty girls dancing. The girls were enjoying themselves too, making money, being fawned over... [Men], their commercial instincts deadened or diminished by happiness, threw on the girls the contents of their wallets which they worked so hard to accumulate. Look, this is how little they mean to me, these brightly coloured pieces of paper. Men came here to debase money.This is a rather sanguine picture of these sorts of place: as Mehta himself knows, they guys are totally exploited and any joy the girls might get is both fleeting and always with the recognition that this is their one shot of avoiding a more desperate way of life. Neither of the dancers he spends a lot of time with is content with the life, both are near the end of their time in the sun. But these sections were really good, in the way that Mehta presents full histories (spending nearly 100 pages on them) of both these characters, and meets their friends, families, partners. Unlike a journalist or other sort of observer, Mehta becomes a full participant in their lives - you get the sense that both regard him as a friend, and he certainly seems to want and try to do a lot for them, to the point you begin to wonder what his own family would make of it all, think it is convenient for him that he has kept his familay away from this life.

I like what he calls movies - "distilleries of pleasure". Again, Mehta is fully engaged: he has gangland contacts with the movies - the two are inextricably mixed, as traditional lenders won't touch the speculative business of movie making, so it is gang money which lets them happen. In quite a nice turn of events, Mehta gets involved in a movie where his gangland contacts provide a degree of authenticity to the movie for which he is scriptwriter.

The fnal section, as if in the search for some form of vicarious repentance for all the other things he gets up to in the book, looks at a sadhu: one who is "taking diksha", giving up all earthly pursuits ("no violence, no untruth, no stealing, no sex, no attachments (to property or people)") in favour of a godly life. Mehta starts this section:

I am sick of meeting murderers. For some years now, I have been actively seeking them out ... to ask them this one question: "What does it fell like to take a human life?" This unbroken catalogue of murder is beginning to wear on meSo he goes to meet a Jain family: because the father is taking diksha, apparently the whole family has to, but they cannot acknowledge each other as family members any longer. The Jains are at the extreme end of ascetism: they cannot take life, to the point they have to stay inside during the rainy season to avoid standing on some sort of bug in a puddle or killing the unity of the water. As sadhu, they're entirely at the mercy of the community for food and shelter - something lacking in a city like Bombay, so they'll need to take to the road.. It is a strange sort of thing to do: while it is definitely a much harder thing than I could ever contemplate, it is an oddly selfish thing, as it is not about helping anyone else, just the one taking diksha. Of course, since they have to give up all attachments, they can't own anything, so there are plenty who benefit from that.

When we were talking about this book at my book club, one of the major points we talked about was the different expectations as to privacy. Mehta says that when the middle class look for accomodation, they must have enough privacy to be able to change their clothes without drawing the curtains. On the other hand, in the slums, there was simply no concept of privacy at all: indeed, Mehta met families who insisted on staying in the slums even when they could afford not to because living in their own house, no matter how modest, would make for a very lonely life.

If this book has defects, they are minor. I suspect that Mehta's fascination with the underworld made this part of the book grow to 300 pages. I think the one thing that annoyed me a little was that every so often, there would be continuity problems - not so much characters coming in without introduction as characters we know quite well being introduced all over again. Apparently, some of the book has its genesis in pieces written for magazines and the like, which probably explains these few clumsy joins in the narrative.

1 Comments:

I read this book...freakin amazing.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home