Grey Gardens

When I saw in the email announcing this movie that it was about part of the JFK clan, I nearly switched off, because I am so not interested. But I did manage to read on, to find out that this was about a very peculiar sub-part of that family: a mother and daughter (both called Edie Bouvior Beales) who had taken themselves away from society and not emerged from their property for 25+ years. For reasons we never learn, they decide to let the Maysles brothers in to film their so called life. It might have something to do with their house being condemned (leading to some very vitriolic commentary by mum in the letters to the editor column in the local press. Maybe, because they knew their time was coming to an end, a record was wanted.

When I saw in the email announcing this movie that it was about part of the JFK clan, I nearly switched off, because I am so not interested. But I did manage to read on, to find out that this was about a very peculiar sub-part of that family: a mother and daughter (both called Edie Bouvior Beales) who had taken themselves away from society and not emerged from their property for 25+ years. For reasons we never learn, they decide to let the Maysles brothers in to film their so called life. It might have something to do with their house being condemned (leading to some very vitriolic commentary by mum in the letters to the editor column in the local press. Maybe, because they knew their time was coming to an end, a record was wanted.

The film certainly comes across as if the access granted to the camera was pretty open - it is a very candid film some have gone so far as to say it is exploiting them, but that's a pretty big call as it assumes they don't know for themselves what to allow. I think they were incrediby brave in letting this movie happen, showing the sadness that can come from forever living in the past, clinging to never acheivable dreams; saying they were exploited diminishes that. In a leter interview, little Edie says "Grey Gardens is a breakthrough to something beautiful and precious called life".

I don't actually know how long we spend in the house: one problem in making a film of this typpe, where there is no plot, no dramatic tension, nothing at all happening really, is deciding when to stop. There was a great line, towards the end, where little Edie says "after a while, cats and raccoons [their only long term companions] get a little boring" which seemed an ideal termination.

We see old photos of them both, they had bright futures, being privileged by their birth, but never got anywhere. The mother's story is a bit murky as to how she became becalmed in the house, a lost romance seems to be at the back of it. Little Edie went out into the world, tried her hand at dancing on Broadway and modelling, stuck it out for six years. About when she turned 30, as the story goes, she had to return home to look after her mum and has never left - but lack of professional success and not finding a man might have something to do with it. At 57, she's still pretty infantalised in terms of aspirations for a relationship, still has some sort of belief, but it must be the "right" man. Bickering about their past life and what might have been forms a large part of their daily activities.

Apart from that, little Edie still persists with her dancing, sunbathes, does very little to attend to the house (which is in a shocking state - not just messy and unclean but with a raccon family in the attic and multiple holes in the walls). It is apparently a 28 room mansion, but they only manage to fill a very limited space.

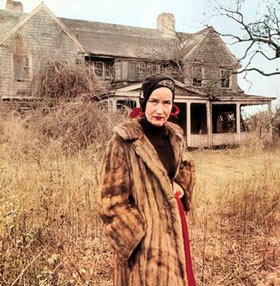

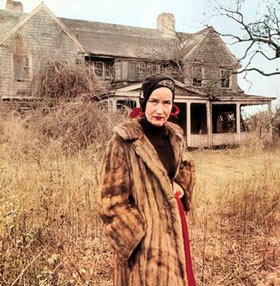

Maybe all the other rooms we don't see are filled up with Edie's fashion - she has a fairly unique style! In the opening scene, we see her wearing the clingy brown tuirtleneck and sheer nun's wimple on her head pictured to the left. She is also wearing a pair of sun pants pinned around her waist over tights of some sort, saying this is the costume she chose after having a big row with her mother, who had insisted on a kimono. She explains the practicality of her clothes: she doesn't like the look of a short skirt, but when it is worn over pants and/or stockings, why then the skirt can be removed and worn as a cape, with the stockings pulled up over the pants (or some such).

Maybe all the other rooms we don't see are filled up with Edie's fashion - she has a fairly unique style! In the opening scene, we see her wearing the clingy brown tuirtleneck and sheer nun's wimple on her head pictured to the left. She is also wearing a pair of sun pants pinned around her waist over tights of some sort, saying this is the costume she chose after having a big row with her mother, who had insisted on a kimono. She explains the practicality of her clothes: she doesn't like the look of a short skirt, but when it is worn over pants and/or stockings, why then the skirt can be removed and worn as a cape, with the stockings pulled up over the pants (or some such).

The movie is apparently a cult classic - #33 on an Entertainment Weekly top 50 classic cult movies: I'd not heard of it until the film society showing, but I can see its underground appeal, without necessarily wanting to join in on the various devout communities about the place devoted to the movie and its stars.

As a footnote: mum died soon after the movie, as she was already 87. Little Edie lived on, even moved out, into New York where she staged a few shows. She died, alone, in an apartment in Florida in 2002.

The Sunday Philosophy Club by Alexander McCall Smith

I didn't like this book - it is a long time since I have actually read a book I didn't like all the way to completion. In fact, I have a pretty good hit rate - I pick a book up, make a pretty snap decision as to whether I'll like it, and then if I think I will, I read it. This is my first failure since The Bridhes of Madison County - that I read because so many people had and were raving about it: it rates as my personal worst. I only finished because I thought that such a turgid mass must have a really great spin at the end to make up for it: it didn't. I finished The Sunday Philosphy Club because people I actually know and like had said good things about it and, while I wasn't blown away, I didn't mind the first in the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series.Precious Ramotswe was perfectly amiable and had a decent homespun moral sense.

I didn't like this book - it is a long time since I have actually read a book I didn't like all the way to completion. In fact, I have a pretty good hit rate - I pick a book up, make a pretty snap decision as to whether I'll like it, and then if I think I will, I read it. This is my first failure since The Bridhes of Madison County - that I read because so many people had and were raving about it: it rates as my personal worst. I only finished because I thought that such a turgid mass must have a really great spin at the end to make up for it: it didn't. I finished The Sunday Philosphy Club because people I actually know and like had said good things about it and, while I wasn't blown away, I didn't mind the first in the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series.Precious Ramotswe was perfectly amiable and had a decent homespun moral sense.

Isabel Dalhousie was just annoying. Some people feel sorry for her, she's quite a lonely lady, she seems to be the sole remaining member of her Sunday Philosophy Club. I still haven't worked out whether she is to be taken seriously or if the work is really satirical (which would make it stronger). Isabel spends her time as the editor of a journal of applied ethics, so we get frequent references to famous philosphers and their take on various things. One of Isabel's major philosophical stances is that one must reflect before reaching judgment, she is quite fulsome in her criticism of those who do not. But blow me down if she decides she doesn't like her niece's new boyfriend because he wears strawberry pink corduroy trousers, or takes an instant dislike to a woman called Minty because she is hard-faced: Isabel then takes great delight in finding others who don't like her. So - there may be an element of pillorying the pretensions of philosphers here, but Isabel is hardly the typical philospher.

The actual plot of the book leads on to other annoyances: Isabel is at the theatre, there has been a performance by the Reykavich Orchestra - her going seems to have been a personal favour on her part, she was shocked to find that they were attempting Stockhasen. No, I don't know either, and it is never explained (reading Wikipedia I get the feeling that he was pretty adventurous but there's a high snob value to dismissing him as last year's news: I also see that he claims that September 11 was a "work of art", Lucifer's best so far). Anyway, there's a lot of thinking going on in her head about the courtesies owed by visiting orchestras, and so on - all subsequent upon her seeing the body of a young man fall from the gods nearby. By page 75 she finally thinks that maybe there was something not quite right about this death, maybe he was pushed and she should investigate. Here's where her instinctive reactions get her into trouble: of course, hard faced Minty is an immediate suspect. So, we spend all but the last two pages pursuing false leads, interpsersed with Isabel's commentary on art. She likes paintings of cats and tulips. Enough said.

I think my major problem with her is that she was just so far removed from the things I'm interested in, although the author has her do things to show she's still in touch, such as going up to a young fellow with a few piercings and asking him about them, as if your average 40 year old inhabitant of Edinburgh will never have seen them before. He is all about not wanting a uniform: she responds with the obvious point that he might simply have adopted another. The only thing she does that I think I would do is go to a talk on Becket.

The other characters didn't help very much: Jamie is the perfect young man, the kind of chap every maiden aunt would want her niece to be with, while she has gone off with the caddish Toby, he of the strawberry cords. Then there are a couple of flatmates of the deceased we see briefly and various people from the financial world, who fill Isabel in on things like insider trading and the relative probity of the Scottish financial world.

Looking over at Amazon, I see my response is hardly unique, although there are plenty who give it five stars.

Hidden (or Caché), a movie by Michael Haneke

Completely coincidentally, this movie also has as part of its structure the continuing tension between the French and Moslems: specifically a situation several decades earlier in which there were a lot of Algerian immigrants and, on one brutal day in 1961, around 200 of them were pushed into the Seine, presumably to drown.

Completely coincidentally, this movie also has as part of its structure the continuing tension between the French and Moslems: specifically a situation several decades earlier in which there were a lot of Algerian immigrants and, on one brutal day in 1961, around 200 of them were pushed into the Seine, presumably to drown.

The film opens with what seems to be a long take of the outside of a suburban house, every so often we see and hear people passing by. It turns out that we are watching a video with Georges (Daniel Auteuil) and Anne (Juliet Binoche). He is the host of a television literature programme - they have an amazing range of bookcases that I'd have loved to explore. They don't, however, seem to be much of a couple - there is very little intimacy between them, no touching at all, and they set about their discussions like a pair of students assigned to do a piece of group work. All the while, the camera is right in there with them - either the camera making the film we are watching or the camera making the film they are watching.

So, this tape has been left on their doorstep and has obviously been filmed by someone sitting in the lane leading to their house. Having something unusual and slightly spooky like this happen proves to insert the point of a pick axe into a fissure of guilt Georges has long suppressed. They get three tapes like this one, then one further tape showing the location of another apartment, together with a few cards - one has a crudely drawn (as if by a child says someone) human head with a blood red tongue protruding, another is of a chicken with a big gash in its neck - and that is enough to unravel our hero.

These send Georges mental: he goes to the apartment shown in the tape, and finds an Algerian fellow, Majid, who his family had taken in as a farm worker all those years ago when he was six. Georges blames Majid for sending the tapes, and simply can't listen to his denial. So, our middle class and well established Georges is threatening Majid with all sorts of dire consequences, yet pretends to his wife that he never found him. Bad move because, sure enough, another tape turns up - making her really wonder what is going on, now that Georges is outed as a liar and a bully. What else is there?

Then their son doesn't come home: of course, Majid has kidnapped him (not!). I think that this is the power of the film: Georges guilt about what he did to Majid 30 years ealier means that he cannot now process reality, thinks that since he is to blame then everything bad that happens must be Majid or his son taking vengeance when, as the son says, he's been educated and simply doesn't think in that way.

The film ends with a scene that shocked pretty much everyone in the theatre - I guessed what was about to happen a mere second before it did - with us left with Mojid and the son both denying anything to do with the video tapes and us no closer to knowing who sent them. Well, me anyway: apparently there is an answer given in the very last shot, but I missed it! In my defence, it was another fairly long take with the credits running, so I had distractions.

I don't however, think the movie is just about Georges and Mojid, but more f a commentaty on contemporary France - people like Georges and those he is interviewing and those who are watching have their comfortable lives on the back of a pretty unsavoury past, features of which are still present. There's a scene in which Georges merrily walks out into the road between two cars, not watching at all, and is nearly skittled by a black man (i.e. immigrant) on a bicycle: Georges self righteously is about to climb all over the fellow on the bike, for daring to be there where he ought not. Luckily Anne intervenes and points out some good sense.

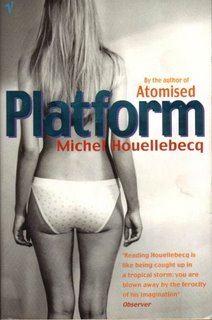

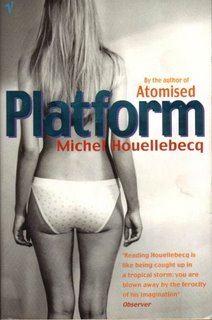

Platform by Michel Houellebecq

He is the bad boy of contemporary French literature, decried as being offensive, over the top in his sexual explicitness and inciting trouble with the numerous followers of Islam in France. The author himself defends his writing as simply reflecting his very dim view as to the modern state of humanity and as being in the same mood as Camus and Celine before him.

He is the bad boy of contemporary French literature, decried as being offensive, over the top in his sexual explicitness and inciting trouble with the numerous followers of Islam in France. The author himself defends his writing as simply reflecting his very dim view as to the modern state of humanity and as being in the same mood as Camus and Celine before him.

When I was reading Platform, my first instinct was to think of Brett Easton Ellis writing about the rampant consumerism of modern society: we simply consume and become brands - we equate a Naomi or a Samuel with a Pepsi or a Honda, and glibly consume both. With Houellebecq, it is sex: on almost every page, there is some form of sexual activity described in matter of fact detail, so that very soon there is nothing special about it at all. There is no emotion, no love, no tenderness, just sex endlessly on tap and best delivered by young Thai prostitutes. Michel says he wants more, even on page one, but in a way that defers belief:I'm not married, either. I've had the opportunity several times, but I never took it. That said, I really love women. It's always been a bit of a regret, for me, being single. It's particularly awkward on holiday. People are suspicious of single men on holiday, after they get to a certain age: they assume that they're selfish, and probably a bit pervy; I can't say they're wrong.

He is 40: these are his thoughts as his father is buried and are typical of his embedded self involment; one redeeming feature is that he is fully aware that he is self involved and disengaged - every so often there is a suggestion that he wishes things were different, but ultimately his lifestyle seems to be a matter of choice for him.

Of course, his father has been killed by a Moslem - this is revealed by a quick Police investigation which finds that dad had been having it off with of his maid. Her incredibly stupid brother "struts round like the guardian of the one true faith" thinking she is a slut and has killed Michel's dad to protect her from the infidel. Given the acute tensions between Moslems and non-Moslems in France, you can understand how this might provoke: he seems to be attacking directly the notion of the middle class that Moslem attitudes and tradtions must be protected, no matter what offense they may give. There is another episode towards the end of the novel where Moslem tradtional belief is blatantly crossed, with another episode of bloodshed in the name of protecting that tradition. He almost dares us to have no respect for these tradtions, in the brutal way in which they are protected.

These are not his only targets - every so often we have a patch of text where Michel (and you wonder about the line between author and narrator in these) goes on about one thing or another - modern capitalistic travel firmsTaking a plane today, regardless of the destination, amounts to being treated like shit for the duration of the flight. Crammed into a ridiculously tiny space from which it is impossible to move ... you are greeted from the outset with a series of embargoes announced by stewardesses sporting fake smiles...

or the ideology of Agatha Christie novels. I think the funnies was when he tries reading some blockbuster fiction - The Firm and Total Control: he finds them so bad that he buries them on the beach.

But the book is really of Michel's navigation of his way through this unsatisfying life - he has some sort of accounting job in the Ministry of Cultural Affairs where he can remain completely disinterested, he says "I am not happy but I aspire to be happy", loves travel brochures and their star system for indicating the intensity of the happiness to expect. He has no friends, gets his kicks with a daily visit to a peepshow, gets along OK with his workmates, probably passes quite successfully as joe average. We don't know how long he has been stuck in this routine, but his father's death changes it all: he takes off on a package tour to Thailand. This part of the book reads a lot like a travelogue - we get a devastating description of his fellow travellers and their various factions, snippets of histroy of wherever he happens to be, personal histories of the people he's talking to and, of course, complete reports of his sexual encounters. Of all the women we meet, Valerie is the one he mentions most frequently, yet he never makes any sort of move on her, despite noticing that she has a spectacular body and takes most trouble to engage with him.

Back home, however, thanks to a chance encounter they do finally get together. He can't actually see why she'd see anything in him, which is actually quite charmingly honest, as he really isn't much of a catch and he is gracious enough to see she is. Clearly, however, she does and for the first time in his life, he finds love - something I think that he has managed to maintain some sort of belief in, despite its elusiveness. All that meaningless sex doesn't mean he has completely shed his innocence (to quote Tim Parks' Judge Savage). So, after they've slept together and talked and he's quizzed her on why she wants to be with her, he comes to this realisation:It was then, somewhat incredulously, that I realised that I was going to see Valerie again, and that we would probably be happy together. It was so unexpected, this joy, that I wanted to cry; I had to change the subject.

Here's where the central ideas of the book, insofar as there are any, come to the fore. Valerie works for a large French package tour company, which is in danger of losing its edge - her job is to find some market niche which has not been inhabited but which, once they occupy it, will give them control for a fair chunk of time. Houellebecq is not afraid to get his hands dirty and write at length about the tourism industry, marketing, how things work in business - something that is completely natural for his characters and sets up a logical foundation for the great idea that Michel, not Valerie, has to rejuvenate the loss making parts of the business - since everyone goes on a package tour with some hope of a fling, that should be a guaranteed feature of the package. And so they start developing and marketing sex tourism - their one big mistake being that their first such venture is to Thailand, this time to that part of Thailand which is most under the thumb of Moslem fundamentalists.

A lot of the reviews of this book don't rate it very highly, some dismiss it completely and my book club members were very mixed in their attitudes. I guess I actually related to Michel in ways that they didnt, because I ended up loving many parts of this book and was forced to tears by my realisation of what the end meant (not that everyone agrees with me on my interpretation, but you can't have everything).

When I saw in the email announcing this movie that it was about part of the JFK clan, I nearly switched off, because I am so not interested. But I did manage to read on, to find out that this was about a very peculiar sub-part of that family: a mother and daughter (both called Edie Bouvior Beales) who had taken themselves away from society and not emerged from their property for 25+ years. For reasons we never learn, they decide to let the Maysles brothers in to film their so called life. It might have something to do with their house being condemned (leading to some very vitriolic commentary by mum in the letters to the editor column in the local press. Maybe, because they knew their time was coming to an end, a record was wanted.

When I saw in the email announcing this movie that it was about part of the JFK clan, I nearly switched off, because I am so not interested. But I did manage to read on, to find out that this was about a very peculiar sub-part of that family: a mother and daughter (both called Edie Bouvior Beales) who had taken themselves away from society and not emerged from their property for 25+ years. For reasons we never learn, they decide to let the Maysles brothers in to film their so called life. It might have something to do with their house being condemned (leading to some very vitriolic commentary by mum in the letters to the editor column in the local press. Maybe, because they knew their time was coming to an end, a record was wanted. Maybe all the other rooms we don't see are filled up with Edie's fashion - she has a fairly unique style! In the opening scene, we see her wearing the clingy brown tuirtleneck and sheer nun's wimple on her head pictured to the left. She is also wearing a pair of sun pants pinned around her waist over tights of some sort, saying this is the costume she chose after having a big row with her mother, who had insisted on a kimono. She explains the practicality of her clothes: she doesn't like the look of a short skirt, but when it is worn over pants and/or stockings, why then the skirt can be removed and worn as a cape, with the stockings pulled up over the pants (or some such).

Maybe all the other rooms we don't see are filled up with Edie's fashion - she has a fairly unique style! In the opening scene, we see her wearing the clingy brown tuirtleneck and sheer nun's wimple on her head pictured to the left. She is also wearing a pair of sun pants pinned around her waist over tights of some sort, saying this is the costume she chose after having a big row with her mother, who had insisted on a kimono. She explains the practicality of her clothes: she doesn't like the look of a short skirt, but when it is worn over pants and/or stockings, why then the skirt can be removed and worn as a cape, with the stockings pulled up over the pants (or some such).