Randoms

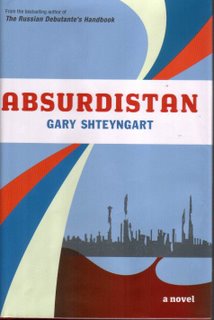

Well, I had very good intentions for this week, which is being cut slightly short by my departure for Melbourne at 12:50 today (around 9 hours away). I did get my comments on Absurdistan up, but I have so many other books I've been wanting to write about. I've held on to Neil Gaiman's Anansi Boys two weeks into the library's "extended loan period" (their way of talking about overdue books) in the thought I'd have something to say, and now they've gone and billed me for it.

Then there was Orhan Pamuk's Snow which had various impacts on me - at one stage I wanted to throw it away, it was so slow and strange and about something that had no interest for me at all (religion). But then I started to pick up on suggestions of a Brechtian theatre of the absurd (not that I know a whole lot about that), and noticed this deeply comic storyline opening up. None of my book club members noticed it, but I think most had given up by that point. But what are you supposed to do but laugh, when you notice that the main character, Ka, is ostensibly organising this big meeting of terrorists of various shades so that he can send their message to the "West", to this so-called big time newspaper editor who is really just a random fellow Ka had bought a coat off. And then you remember that Ka had been looking for a way to get the father of his girlfriend out of the hotel, so he and the girlfriend can have sex. Sure enough, Dad is off to the meeting, and its all on (or off, really). And then there are all the fun and games he has with the secret police operatives - such as when a fellow comes into a cafe looking for another. The cafe owner points to a bloke in a corner and suggests that since he's an undercover cop tailing the fellow being looked for, he might be the right person to ask.

And before that, well there was the fantastic Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, about a hugely dysfunctional group of "soldiers" led by this often naked, pale white, fat fellow called the Judge, down through the desert at the top of Mexico not long after the mid 19th century cessation of war. At first, the soldiers are maybe doing the right thing - at least they're working for the government of the area, clearing it of Indians, scalping them as proof. But their allegiances change, they develop a taste for the work and start doing it with no master. All narrated in MacCormac's flat prose, where the great majority of conjunctions are formed by the word "and", so that there's little sense of motivation, causation, or valorisation, just one thing after the other, good followed by bad, with an unsparing account of the bad things they encounter. The worst I remember was the tree full of the bodies of dead babies.

And Beckett! He's been stalking me for years, a name I knew I'd have to read but never got around to. Not, that is, until his poem Malecoda. This was a poem that made very little sense when first I read it: indeed I read it several times but meaning was elusive. Have a go:

thrice he cameKnowing that Malecoda came out of the Inferno helped a little, as it helps to decode some of the more obscure words, and of course that particular Canto ends with a fart. And so, the poem resolves into one in three movements, the three occasions on which the undertaker came in response to the death of Beckett's father - the first "to measure" at which time, the devil's assistant also "signals". This is such an affront to Beckett's sense of the solemnity of the occasion, and one he knows will be deeply disturbing to his mother that he loses track of his language, in his concern to protect her - she may hear, but there's no need for her to see. I had a two hour class analysing just this poem, at the end of which I felt a real connection with Beckett; his feelings about the consoling effect of religion, the traditional forms of a funeral and of art (i.e. that they were not enough) made me think about my own father's funeral, and how we had to do something unconventional for him, as a Church-based thing simply would not have worked. So, we took him down to a bend in the river he loved, and had the fellow running the Salvation Army kid's adventure centre conduct a service, and then we had a party.

the undertaker's man

impassable behind his scrutal bowler

to measure

is he not paid to measure

this incorruptible in the vestibule

this malebranca knee deep in the lilies

Malacoda knee-deep in the lilies

Malacoda for all the expert awe

that felts his perineum mutes his signal

sighing up through the heavy air

must it be it must be it must be

find the weeds engage them in the garden

hear she may see she need not

to coffin

with assistant ungulata

find the weeds engage their attention

hear she must see she need not

to cover

to be sure cover cover all over

your targe allow me hold your sulphur

divine dogday glass set fair

stay Scarmilion stay stay

lay this Huysum on the box

mind the imago it is he

hear she must see she must

all aboard all souls

half-mast aye aye

nay

Once started on Beckett, I then read Molloy which, with its references to big policemen, bicycles, the Irish country-side, mal-functioning legs and the like provided strong reminders of The Third Policemen, upon which I will be seriously engaged during my ten days in Melbourne. I did have other plans, as I had thought that Melbourne, with its emphasis on the cultural life, would have a fantastic Writers' Festival but, upon seeing the programme, I was horribly disappointed - none of the authors I had hoped might come, hardly an author I recognise at all. While it could be a lot of fun to sit in on a lot of sessions featuring unheard of authors, it is not something I am willing to do when each session costs $20 or more. So, I will take my laptop and sit in the State Library of Victoria of a morning, and try to put my thoughts and notes into some sort of coherent order. I have established that they have one of the very few copies of Eimar O'Duffy's works to have surved until now in Australasia (there are officially none in New Zealand), and the thought of reading The Spacious Adventures of the Man in the Street is a pleasurable one. I have also established quite a list of interesting cafes and restaurants to check out, and have an obligation to write a review of Edward St Aubyn's Mother's Milk so should not lack for things to do.