Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles

This is the latest film from the very prolific mainland Chinese film-maker, Zhang Yimou, and quite a departure from his more recent works like House of Flying Daggers. I probably should have spent a little time reading about him before seeing the film, because I may have missed things, but it seems to me that this one was far more realistic, eschewing the highly symbolic and magical elements. No specific colours stuck out as carrying symbolic value and, unlike virtually all of his movies, there was no female hero. Nor is there any fighting at all. Instead, he seems to have given full reign to what one commentator has called the "son's gaze" but in a very conservative way.

After a ten year estrangement - we never really learn why but it seems to have been caused by the death of the mother - Takada learns that his son is very ill. (I think this is different as well - the central characters are Japanese.) Nonetheless, the son (Ken-ichi) refuses to see his father. Rie, the daughter in law, tells Takada that Ken-ichi has spent time in China, making a movie about a mask opera which celebrates one Lord Guan (who is the personification of loyalty), Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles, and has made many friends there. Dad gets it in his mind that to be reconciled with his son, he should go to Yunnan Province to meet his son's friends and to finish his work for him. He speaks no Chinese and in the small towns to which his mission takes him, he finds no-one who speaks Japanase. So, he has a translator - I'm not sure if it was an intentional joke, but it turns out that his translator is called lingo, and speaks about as much Japanese as I do:

Dad's mission turns out to be much more complicated that at first anticipated - his principal singer Li has been imprisoned, and won't be let out for three years. After recourse to his uselesss translator and another back in the city, he manages to get permission from the very obliging prison governor to film Li singing in prison. It turns out that Li is heart-broken because he has this 8 year old son back in his home village whom he has never seen but just learnt about. He can only perform once he's seen his son. So, off Takata goes to the Stone village - an actual town that sits on top of a huge rock about 110 km from the prison. The journey is more than a little trippy, with some amazing geology. Of course, the village elders are all happy to have the son go see his father, and they have a village dinner, in which the main street is set up as a very long dining table.

Dad's mission turns out to be much more complicated that at first anticipated - his principal singer Li has been imprisoned, and won't be let out for three years. After recourse to his uselesss translator and another back in the city, he manages to get permission from the very obliging prison governor to film Li singing in prison. It turns out that Li is heart-broken because he has this 8 year old son back in his home village whom he has never seen but just learnt about. He can only perform once he's seen his son. So, off Takata goes to the Stone village - an actual town that sits on top of a huge rock about 110 km from the prison. The journey is more than a little trippy, with some amazing geology. Of course, the village elders are all happy to have the son go see his father, and they have a village dinner, in which the main street is set up as a very long dining table.

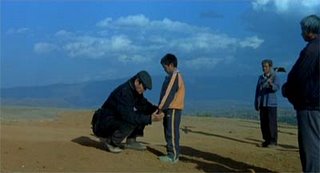

But it is here where the son's gaze idea becomes important, on at least a couple of levels. It turns out that Ken-ichi wasn't that popular here anyway, few even know who he is let alone admit to being his friends and Ken-ichi was only making the movie because it was something to do. Dad should scrap the idea and come home - but his conscience is so affected, and his idea of what he has to do to be loyal is so located in getting this movie done that he can't give up. It also transpires that Li's son doesn't want to meet his father - he runs away, leading to him and Takata getting lost in this area of rock formations:

- they'd be stalactites if they were in a cave, but they're not - just an area of very high and very pointy spikes of rock. They bond, and Takata wants the village to honour the boy's wishes as regards seeing his father:

- they'd be stalactites if they were in a cave, but they're not - just an area of very high and very pointy spikes of rock. They bond, and Takata wants the village to honour the boy's wishes as regards seeing his father:

I think there is something being said here about the old ways having to give way to the new and, indeed, that outside voices will have their part to play in sorting out the new.

I think there is something being said here about the old ways having to give way to the new and, indeed, that outside voices will have their part to play in sorting out the new.

Overall, it is a very gentle film, with a very strong sense of missed communications but with the possibility that if we work at it, we can get there - a lesson Takata is just now learning in relation to his son, when it really is too late.

Tsotsi

This movie was nothing like the movie I was expecting, but then I didn't really know much about it, except that it had been compared to City of Gods and had won the Oscar for International Film. I thought it was going to be about some young thug in a tough part of some South African city, doing what he needed to survive. Certainly, the opening scenes confirmed those expectations: he and his gang are on a train, they circle a man in a suit who evidently has some money and Tsotsi uses a long screwdriver which has been sharpened to a point to kill the man. It didn't like he had much money, just his paypacket, but life is cheap. Then there was a big fight in which Tsotsi nearly killed Boston, one of his guys, because Boston wants to know if Tsotsi knows what it means to be decent. Tsotsi takes off by himself and does a carjacking. This is all in the first ten minutes or so of the movie.But it turns out that the car he's taken has a passenger - the infant shown to the left. As Tsotsi is cleaning out the car, we're left on edge: what is he going to do with this baby, is he going to be so monstrous as to kill it? It is certainly possible, given what we know of him. But no: instead, he takes care of the baby, even gives it his own name. Pretty much everything he does from the time he takes the baby back to his shipping container house is to protect the baby. Sure, some of what he does is violent - he even kills one of his own men, but there is a good purpose to what he's doing. He also intimidates one of the local village women, Miriam, holds a gun to her head, so she'll feed the baby because Tsotsi is woefully out of his depth when it comes to caring for a child. He feeds it condensed milk, which he fails to clean off its face, and is surprised when he comes home hours later to find the baby covered in huge ants.But the film is about him coming right, about him working stuff out. I went with quite a big group of people, and in our discussions afterwards, we decided that the movie managed to be sentimental, without going too far. Our biggest disagreement was over a scene in which he pursues this handicapped fellow into some sort of empty car parking building. Some thought he was going to kill the fellow but changed his mind. I thought he had two reasons - one a bit silly: he had this kid with no idea how to care for it, and here's this fellow with a nice wheeled contraption which might function as a kind of pram. More seriously, I think he was genuinely curious, he really did want to know what made this fellow just stick at life, awful as it looked. Tsotsi tells the fellow about a dog with a broken back which still had the will to live - it turns out that it was Tsotsi's own dog, stomped on by his brute of a father. That was it, in terms of Tsotsi having any kind of family - he ran away and lived in the upper left one of a pile of culverts.When we catch up with him, Tsotsi is looking, not so much for a way forward, but a reason for going forward. Eventually he goes far enough down that path to work out that the baby has to be returned to its mother - with a bit of nudging from the woman he co-opted to feed him. Of course, the police are all over the show as he's trying to give the kid back, and there was so much potential for things to go wrong, with hotheaded arned cops, and a very nervous Tsotsi (he's still only 16).In terms of cinematography, the most obvious thing is the general lack of colour - when they're out of the city, everything is dusty and insde there's a strong sepia toning. The only place with any sort of colour is Miriam's house - she wears colourful clothing and makes hanging ornaments out of bits of coloured glass (at least she does when she's happy - the rusty one was when she was not happy, possibly when her husband died in a random mugging).

This movie was nothing like the movie I was expecting, but then I didn't really know much about it, except that it had been compared to City of Gods and had won the Oscar for International Film. I thought it was going to be about some young thug in a tough part of some South African city, doing what he needed to survive. Certainly, the opening scenes confirmed those expectations: he and his gang are on a train, they circle a man in a suit who evidently has some money and Tsotsi uses a long screwdriver which has been sharpened to a point to kill the man. It didn't like he had much money, just his paypacket, but life is cheap. Then there was a big fight in which Tsotsi nearly killed Boston, one of his guys, because Boston wants to know if Tsotsi knows what it means to be decent. Tsotsi takes off by himself and does a carjacking. This is all in the first ten minutes or so of the movie.But it turns out that the car he's taken has a passenger - the infant shown to the left. As Tsotsi is cleaning out the car, we're left on edge: what is he going to do with this baby, is he going to be so monstrous as to kill it? It is certainly possible, given what we know of him. But no: instead, he takes care of the baby, even gives it his own name. Pretty much everything he does from the time he takes the baby back to his shipping container house is to protect the baby. Sure, some of what he does is violent - he even kills one of his own men, but there is a good purpose to what he's doing. He also intimidates one of the local village women, Miriam, holds a gun to her head, so she'll feed the baby because Tsotsi is woefully out of his depth when it comes to caring for a child. He feeds it condensed milk, which he fails to clean off its face, and is surprised when he comes home hours later to find the baby covered in huge ants.But the film is about him coming right, about him working stuff out. I went with quite a big group of people, and in our discussions afterwards, we decided that the movie managed to be sentimental, without going too far. Our biggest disagreement was over a scene in which he pursues this handicapped fellow into some sort of empty car parking building. Some thought he was going to kill the fellow but changed his mind. I thought he had two reasons - one a bit silly: he had this kid with no idea how to care for it, and here's this fellow with a nice wheeled contraption which might function as a kind of pram. More seriously, I think he was genuinely curious, he really did want to know what made this fellow just stick at life, awful as it looked. Tsotsi tells the fellow about a dog with a broken back which still had the will to live - it turns out that it was Tsotsi's own dog, stomped on by his brute of a father. That was it, in terms of Tsotsi having any kind of family - he ran away and lived in the upper left one of a pile of culverts.When we catch up with him, Tsotsi is looking, not so much for a way forward, but a reason for going forward. Eventually he goes far enough down that path to work out that the baby has to be returned to its mother - with a bit of nudging from the woman he co-opted to feed him. Of course, the police are all over the show as he's trying to give the kid back, and there was so much potential for things to go wrong, with hotheaded arned cops, and a very nervous Tsotsi (he's still only 16).In terms of cinematography, the most obvious thing is the general lack of colour - when they're out of the city, everything is dusty and insde there's a strong sepia toning. The only place with any sort of colour is Miriam's house - she wears colourful clothing and makes hanging ornaments out of bits of coloured glass (at least she does when she's happy - the rusty one was when she was not happy, possibly when her husband died in a random mugging).

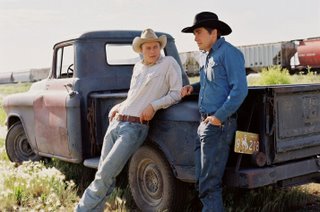

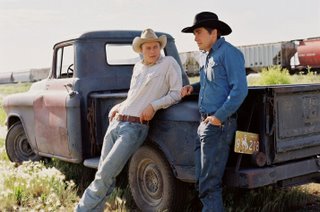

Brokeback Mountain

It took me a fair while, but I finally saw this movie. I really don't get why people are calling it the greatest love story of all time - maybe they've never heard of Romeo and Juliet. Sure, there was all sorts of suppressed passion going on, and the social circumstances got in the way a little, but their love was pretty commonplace, but for the fact it was between two men. It isn't like Ennis gave into to Jack's wish that they go away and start some farm together.At one point, around half an hour into the movie, when one of the audience members left, I was beginning to wonder about this movie, whether I should bother to stay. Ultimately, I am glad I did - I have come to appreciate the way that Ang Lee very gradually built up the complexity, starting with the pastoral scenes up Brokeback mountain where everything was pretty simple, to the point where both men have their respective families and are embedded in a network of lies, necessary so that they can get to see each other every so often. Then, everything became so simple again for Ennis: he could finally act out his love for Jack, even if it was too late. There was some fine acting from the two male leads, even if they played the two most boring men I've ever watched - quite a risk for Ang Lee to take. Ennis was such a hugely buttoned down character, with all sortrs of things being suppressed. Their last fishing trip, when they realise what their relationship had cost them and how little actual relationshipo they had had was pure gold. Ennis in particular was a man of very few words - he gave his entore life story in a handful of sentences, and it was about as big a piece of talking he'd ever done. But, like his daughter, what words he did use counted.

It took me a fair while, but I finally saw this movie. I really don't get why people are calling it the greatest love story of all time - maybe they've never heard of Romeo and Juliet. Sure, there was all sorts of suppressed passion going on, and the social circumstances got in the way a little, but their love was pretty commonplace, but for the fact it was between two men. It isn't like Ennis gave into to Jack's wish that they go away and start some farm together.At one point, around half an hour into the movie, when one of the audience members left, I was beginning to wonder about this movie, whether I should bother to stay. Ultimately, I am glad I did - I have come to appreciate the way that Ang Lee very gradually built up the complexity, starting with the pastoral scenes up Brokeback mountain where everything was pretty simple, to the point where both men have their respective families and are embedded in a network of lies, necessary so that they can get to see each other every so often. Then, everything became so simple again for Ennis: he could finally act out his love for Jack, even if it was too late. There was some fine acting from the two male leads, even if they played the two most boring men I've ever watched - quite a risk for Ang Lee to take. Ennis was such a hugely buttoned down character, with all sortrs of things being suppressed. Their last fishing trip, when they realise what their relationship had cost them and how little actual relationshipo they had had was pure gold. Ennis in particular was a man of very few words - he gave his entore life story in a handful of sentences, and it was about as big a piece of talking he'd ever done. But, like his daughter, what words he did use counted.

For me, the brilliant part of the movie was when they were both navigating their way through their relationships with their wives - particularly intriguing was the situation with Ennis and Alma, as she knew exactly what Ennis and Jack were up to, and just sucked it in for so long - maybe because of Ennis's violence, which was never far from the surface, a mis-direction of the passion he felt for Jack. But there was great stuff to see in Jack's situation, too: I think my favourite scene in the whole movie was their thanksgiving, when Jack and his dad were battling for control of the turkey, the TV, the family. Then, when Jack exploded at his father in law, there was Lureen's sly smile of approval. No such fights in the Del Mar household: the turkey is being cut with an electric knife, and not by Ennis.

I think for me, rather than the big love story thing between Jack and Ennis, the thing that will make me get this movie out when it hits DVD and watch it again will be to pick up on the other details built into the movie, details that I'll have missed but add their own little bit of colour to the story - something Ang Lee seems to specialise in.

Maurice Gee - Blindsight

I really do not know how this has happened: Maurice Gee is reputed to be New Zealand's finest writer, Blindsight is his sixteenth book, and yet this is the first I have read by him. Sure, I have seen two films based on his novels (In My Father's Den and Fracture) but that is not the same thing. Maybe if I was more familiar with his work, the end would not have come as such a surprise.

I really do not know how this has happened: Maurice Gee is reputed to be New Zealand's finest writer, Blindsight is his sixteenth book, and yet this is the first I have read by him. Sure, I have seen two films based on his novels (In My Father's Den and Fracture) but that is not the same thing. Maybe if I was more familiar with his work, the end would not have come as such a surprise.

Alice and Gordon Ferry are siblings, they grow up in the 1930's and 1940's in "Loomis", a fictional town in West Auckland closely based on Henderson. I have no idea why he uses the disguise: as I read the details of this twon, I became more and more convinced it must have been Henderson and all the other locations in the novel are real. Hell, even "Gordon" is real: it is no spoiler to say that through the vagaries of life, he ends up homeless on the streets of Wellington as we are told this in the first two pages. Several of his biographic details are borrowed from a man known as "bucket man", who died in about 2003.

In the meantime, Alice has become famous in her own academic discipline - mycology - and has been very happily married to Neville. There is one central event, however, which has a huge impact on the novel: she has a very unsatisfactory and obsessive affair with Richie. When she learns just how unsatisfactory, she falls apart, for months. The novel is really about her life, with particular focus on her relationship with Gordon. At the same time she was mired in depression, he was going through troubles of his own, from which he never recovered. For many years, she has no idea where he is or what he is doing: when a friend of her father's tells her he has become bucket man, she moves to Wellington to at least be near him. It is of some comfort to her, although he is never aware she is there - not that she doesn't try.

I thought the part where she tracks his movements and finds out how he is living was particularly moving. I think the temptation would be strong to impose one's own standards on him, put him in a home somewhere - either as an explosion of a do-gooder mentality or to save oneself from embarrassment. Alice, however, listens to what she is told by those who know him in his new incarnation (where his only vocabulary is "hello" and "thank you" and he keeps his eyes glued to the ground): terribly sad, but she recognises he has a delicate balance which would only be disturned by people meddling.

The other key player is Adrian - a cool dude who has a job as barista in a funky Cuba Street cafe and plays the double-bass: He has a huge stringed instrument: a double-bass. It beats like a heart, sometimes doing just enough to keep alive, at other times excited by love or lust or hunger of its own capabilities. Adrian plays his instrument well. He tells me the bass - such an improbable beast - can't stand alone for very long. Its job, he says, is more like stitching, even when it beats hard and fast. It fastens things together, the sort of instrument, I think, Gordon may have chosen.

Adrian has been looking for Alice for a while: she is Gordon's sister; he is his grandson who made a promise to his dying father to track Gordon down to pass on his son's love. His presence in Alice's life is what leads to her recounting this tale and her ultimate story - I couldn't believe this had been withheld from us until the last couple of pages.

36 Quai des Orfèvres

I found this movie to be a very disturbing one, simply because there was so much violence, which was used simply to gain the ends of the people involved - the picture to the side is of a party like none to which I have ever been inviated (thankfully). Had I known of the level of violence and darkness, I may well not have gone, but a mild mannered colleague of mine had said she was going to see it. I think I am glad I did.

I found this movie to be a very disturbing one, simply because there was so much violence, which was used simply to gain the ends of the people involved - the picture to the side is of a party like none to which I have ever been inviated (thankfully). Had I known of the level of violence and darkness, I may well not have gone, but a mild mannered colleague of mine had said she was going to see it. I think I am glad I did.

There are basically two stories going on: a gang has been established to take the contents of security vans carrying cash - we see this happen once: the gang simply drives in front of the cash van and opens fire on them until they stop. So, one story is about the efforts of the Police (based at the address in the film's title) to stop this gang.

The other story is about what the Police are willing to do in order to stop them. To add spice, the boss's job is up for grabs: whichever of Vlink (Auteuil - who I last saw in Closet, where he pretended to be gay in order to be protected from a firing by human rights law) or Klein (Dépardieu) can stop (not bring to justice, just stop) the van gang will be promoted. Neither are exactly squeaky clean: Vlink enters into a Faustian pact with an informer which gets him the identity of the leaders of the gang. Thereafter, he does act as we would expect a good cop to; staking out the gang, setting up a bust and so on. But he has set in train a chain of events which will lead to several fatalities, for which the film builds in enough of a backstory for them to really matter. The main actor in these events is Klein who, it seems, will stop at nothing. His own wife has no faith in his abilities as a cop or a man.

These two are, of course, the senior leading men in French cinema, and they bring a lot to their roles. Added verisimilitude is provided by the fact that there was some basis in reality and that the director is a former policeman. So, plenty of gritty action, good cinematography, very real bullet sounds. About half way through, I had the thought "its not exactly a love story" and yet it turned into one. Vlink is fiercely protective of his relationship with his wife (who may have a history with Klein - I tend to think she did). So keen is he to see her while he is locked up that he procures a couple of guns (I guess he had good contacts) and holds his captors and investigating judge captive so he can see her: once done, he goes back inside quite cheerfully.

The end came in a sort of final showdown between the Vlink and Klein, but resisted the obvious. I think that is what I most liked about this film, they way it developed complexity rather than relying upon a formulaic good v evil: here, everyone is implicated, more or less, in evil. The one possible exception is the rookie cop, Ève Verhagen (Catherine Marchal), who wants to learn from Klein. She ends up so disgusted with his methods that she accepts posting to a complaints desk in the boonies rather than work any longer with him.

Tash Aw - The Harmony Silk Factory

You would think that, what with the years I have spent hanging out with Malaysion people, trying to marry one even, loving Malaysian food and even visiting Malaysia I would have read some Malaysian fiction by now. Hell, the only book I can recall reading which is even about Malaysia is Anthony Burgess's Malayan Trilogy. Tash Aw has more claim to be a Malaysian writer than any other I have read, yet he is Taiwanese and only spent his teenage years in Malaysai before moving to England. It turns out he's read about as many Malaysian authors as I have, and he namechecks authors such as Melville, Flaubert, Nabokov and Steinbeck is his heroes. He has nonetheless set this novel fair and square in Malaysia. A bit of attention from the international press saw him garner a cool half million pound advance for it.

You would think that, what with the years I have spent hanging out with Malaysion people, trying to marry one even, loving Malaysian food and even visiting Malaysia I would have read some Malaysian fiction by now. Hell, the only book I can recall reading which is even about Malaysia is Anthony Burgess's Malayan Trilogy. Tash Aw has more claim to be a Malaysian writer than any other I have read, yet he is Taiwanese and only spent his teenage years in Malaysai before moving to England. It turns out he's read about as many Malaysian authors as I have, and he namechecks authors such as Melville, Flaubert, Nabokov and Steinbeck is his heroes. He has nonetheless set this novel fair and square in Malaysia. A bit of attention from the international press saw him garner a cool half million pound advance for it.

The central focus is on one Johnny (apparently taken from Johnny Weissmuller, better known as Tarzan) Lim, a Chinese Malaysian, who runs the Harmony Silk Factory, which is really a modest shop selling textiles. Curiously enough, very little time is spent with these particular premises. A major question hangs over Johnny: did he collaborate with the Japanese when they invaded Malaysia in 1941. His son, Jasper, is convinced that he did and that he is a rogue - this is revealed in the first third of the novel, in which he is the narrator. That take, however, is revealed to be somewhat contingent and subjective, by the next two sections, narrated in turn by Johnny's wife and friend. I ended up simply not knowing what the truth was, and I suspect that is the point, that knowing the truth is always difficult, if not impossible.

For Jasper, this task is doubly difficult: knowing one's father might be the hardest thing one can do and he has decided that the only true thing his father ever said to him is that death erases all traces of life. Of course, by recording the life in a novel, that one true thing is contradicted. To Jasper, his father is a "liar, a cheat, a traitor, and a skirt chaser of the very highest order" - but he only detects his father's "streak of malice" when he is 18 and is leaving home. His dad volunteers to drive him and starts musing about Paradise: I thought, perhaps my father is capable of appreciating beauty; perhaps he is not completely black-hearted and mean after all. In the midst of the downpour I began to feel guilty that I had judged him harshly all these years. I was scared, too - scared of discovering someone I had never known, a different father from the one I had grown up with. But then I heard a sharp slap, and saw that he had swatted a mosquito on his neck "Bastard" he spat as he walked back to the car. His voice was as hard and cold as it always had been, and his eyes were set in anger. As we drove away, I knew that I had been mistaken. That tender moment had been a mere aberration...

Jasper is trying to set down his father's story as a means of achieving personal peace and does a nice job of telling about the Kinta Valley. From Jasper, we learn of Johnny's amazing ability with his hands in getting machinery to work and of his developing relationship with Tiger Tan - boss of a textile firm and organiser of the local communist party. Johnny, of course, is Tiger's successor when Tiger is shot to death (despite all the speculation about who shot him and the clear gains Johnny made from his death, Jaspaer does not accuse his father of this) and becomes the big man of the community. His business takes him to the doors of the local magnate, where for the first time, our man is completely out of his depth. Nonetheless after a "courtship" in which he is simply carried along by events and expectations, he marries the daugher, Snow. She dies the day of Jasper's birth and the day of Johnny's treachery to his people, at least according to Jasper. The facts were that a secret meeting of all the local Communist resistance to the Japanese occupation was organised by Johnny, the Japanese found out about it and killed or arrested all but Johnny, who had established a form of accomodation with the Japanese leadership for the survival of the local people. During this period, Johnny built the Harmony Silk Factory and became propserous. His son accuses him of tipping the Japanese off, but we will never know the truth of that.

This portion of the book is beautifully written, polished prose with a very smooth finish, quite surprising for someone's first published work. The next portion is Snow's diary for a two-month period, in which she is explaining for herself why she has decided to leave Johnny: it immediately casts doubt on Jasper's, as it becomes clear her father is an intimate of the leader of the Japanese occupying their area (Kunichika). There was an interesting piece of foreshadowing in Johnny's account: he at age 12 wanted his father to take him to the Seven Maiden Islands - Johnny refuses "I hate islands". It turns out, that is where he spent a belated honeymoon with Snow and his mate Peter. Just to add interest, they were accompanied by Honey, a friend of Snow's father who thinks Peter is a "vulgar and florid" embarrasment for whom he has to apologise, and Kunichika. Interesting way to take a honeymoon! This trip forms much of the substance of Snow's diary entries - a long journey up through mysterious rainforest to a destination with mystical significance, even if no-one but the Japanese know quite where they are. The trip is pretty much a disaster - the boat breaks down, there are horrible storms, Johnny nearly dies, one of the party does die, there is increasing tension among the travellers - but there is one beautiful moment, when Peter organises a dinner party for his birthday. Entirely appropriately to the circumstances, he sings from Don Giovanni - the bride being stolen from her husband, with Kunichika being the thief. Still think Johnny is going to sell out to Kunichika?

The final section is narrated by Peter, in which he recounts his time with Johnny, interspersed with accounts of some gardening project he has, still in Malaysia 60 years later. He first encounters Johnny reading Shelley in some Singapore bar. Peter follows him up into the Valley and is hooked, numbed even, by Snow as soon as he sees her. Still, he can talk with Johnny, and we for the first time hear an account, at least purporting to be from Johnny, as to his relationship with the communists and the Japanese: "I would rather be betrayed than betray someone else". Much of his part is taken up with his version of the trip to the Seven Maidens, although it too is very subjective, thanks to his affection for Johnny, his love for Snow, his hatred of Honey and his jealousy of Kunichika.

There is another dimension to this novel: Malaysia is a kind of Paradise, over which first the Chines, then the British and finally the Japanese have taken dominion - in much the same way as Johnny and Peter (who is the "good" way of being British, unlike Honey's way) have to give way to Kunichika. This process is fatal for Malaysia.

Dad's mission turns out to be much more complicated that at first anticipated - his principal singer Li has been imprisoned, and won't be let out for three years. After recourse to his uselesss translator and another back in the city, he manages to get permission from the very obliging prison governor to film Li singing in prison. It turns out that Li is heart-broken because he has this 8 year old son back in his home village whom he has never seen but just learnt about. He can only perform once he's seen his son. So, off Takata goes to the Stone village - an actual town that sits on top of a huge rock about 110 km from the prison. The journey is more than a little trippy, with some amazing geology. Of course, the village elders are all happy to have the son go see his father, and they have a village dinner, in which the main street is set up as a very long dining table.

Dad's mission turns out to be much more complicated that at first anticipated - his principal singer Li has been imprisoned, and won't be let out for three years. After recourse to his uselesss translator and another back in the city, he manages to get permission from the very obliging prison governor to film Li singing in prison. It turns out that Li is heart-broken because he has this 8 year old son back in his home village whom he has never seen but just learnt about. He can only perform once he's seen his son. So, off Takata goes to the Stone village - an actual town that sits on top of a huge rock about 110 km from the prison. The journey is more than a little trippy, with some amazing geology. Of course, the village elders are all happy to have the son go see his father, and they have a village dinner, in which the main street is set up as a very long dining table. - they'd be stalactites if they were in a cave, but they're not - just an area of very high and very pointy spikes of rock. They bond, and Takata wants the village to honour the boy's wishes as regards seeing his father:

- they'd be stalactites if they were in a cave, but they're not - just an area of very high and very pointy spikes of rock. They bond, and Takata wants the village to honour the boy's wishes as regards seeing his father: