Shortbus

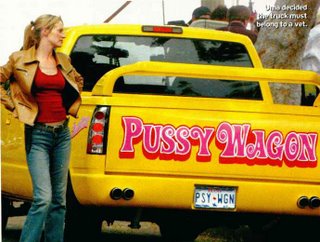

This is the second movie by John Cameron Mitchell, after his 2001 effort, Hedwig and the Angry Itch, a movie I must see now. The title is ostensibly a reference to a bus which is not the traditional yellow school bus, and to a rather adventurous underground New York club

- it is a hangout, performance venue, where people sing songs about feeling upside down by getting quite literal about it and, most important, a place where people have sex. I think it is also important that a short bus is used to transport those needing special education (or, as the urban dictionary puts it less kindly, retards). I think this sense of something missing to the characters is an important theme for the movie.

- it is a hangout, performance venue, where people sing songs about feeling upside down by getting quite literal about it and, most important, a place where people have sex. I think it is also important that a short bus is used to transport those needing special education (or, as the urban dictionary puts it less kindly, retards). I think this sense of something missing to the characters is an important theme for the movie.It would be impossible to talk about this movie without referencing the sex, as there was a lot of it, the participants were rather focussed on its role in their lives, and it too was thematically important to the movie. Oddly enough, the only thing I found to be particularly disturbing (I won't go into details) happened off-screen and was not about sex at all. I did become a bit worried by it: as I was waiting, some people sat down behind me, saying it was time they got themselves some porn. I was beginning to wonder if it was going to be like Michael Winterbottom's 9 Songs, which featured plenty of unrehearsed sex and not much else (apparently - I've not seen it). This was not helped by the opening scenes: we have one fellow trying to position himself so that he could give himself a blowjob (with a fellow looking on from an adjoining apartment, too surprised (not shocked, I don't think) to keep up his photography), we have a dominatrix whacking a fellow who had been dressed and acting like a nerdy school boy and we have a straight couple engaged in sex, in many positions and at great speed.

I need not have worried: this was a wonderful movie. Sure, there was a lot of sex, all shot without the use of blue screens or any other such technology, but ultimately, this was an enquiry into the conections between its characters which went well beyond the sexual.

The woman in the straight couple is Sofia: she is a couples counsellor (who refuses to accept the label sex therapist) who, despite her long and vigourous marriage to Rob, has yet to achieve an orgasm. The fellow playing solo is James, who is in a long term relationship with Jamie: they are seeing Sofia in order to figure out what to do with their relationship. James is a depressive and is probably not as devoted to Jamie as the converse: Jamie is intent on saving the relationship, and is wondering about loving others as a way to salvage it.

Sure, that's an old storylline and has a fresh resolution here. The domanitrix, Severin (or Jennifer Aniston - I mean that's her name, she's not played by her) has trouble connecting, has never had any real relationship with another human being.

Sure, that's an old storylline and has a fresh resolution here. The domanitrix, Severin (or Jennifer Aniston - I mean that's her name, she's not played by her) has trouble connecting, has never had any real relationship with another human being.So, the movie is about the pathways these damaged people (well, they at least feel like damaged goods) have to take. Shortbus provides the answers: Sofia meets Severin,

and they form a mutual support group, meeting every night in a sensory deprivation tank. This reminds me of something else the movie was pretty good at doing, at highlighting people's pretentions (such as Sofia eschewing a chair in favour of a swiss ball, and the sickmaking way in which Sofia and her husband would talk with each other when conflict resolution was needed): inside Shortbus, they all fade away.

There's a kind of framing device in order to show us the movie is conscious of its own fictional nature but, even so, there was an incredible sense of freshness to the scenes. I think this was partly because the crew developed the story lines themselves, improvising as they went along, and also quite a few of the supporting roles were people from the NY underground (freak?) scene playing themselves. So, we could see they were having an enormous amount of quite silly fun - particularly when James and Jamie brought Ceth into their midst. Oh, and then Sofia gives her husband the remote control to a vibrating egg: if he wants to say hi, all he needs to do is push the button. Of course, he's not really having a good time, so sits it out, with said remote in his rear pocket - with resulting hilarious results, because Sofia IS getting into the swing of it.

But there was an incredible degree of tenderness at the same time, in fact I'd say this was the prevailing mood: at several points, I found myself crying, as things worked out for these people. I loved the scenes where Sofia is looking on, not knowing how to respond, at what is basically an orgy - but there was one woman, she seemed cool, who noticed Sofia's presence and seemed to be suggestive of a future path.

There is also a political agenda: the filmmaker sees it as a small act of resistance against Bush's America, trying to be a reminder that there are still good things, New York is still a refuge for those who don't fit elsewhere, is a place for personal expression, not just tolerance but acceptance of diversity.