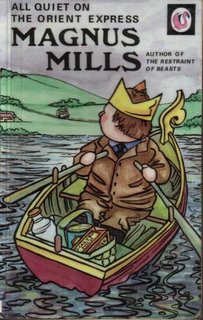

All Quiet On the Orient Express by Magness Mills

He’s a strange one, is Mr Mills. He speaks to us from the perspective of someone transplanted into a rural working class environment, so in his first novel The Restraint of Beasts we joined an English fellow who had been put in charge of a pair of truly terrible Scottish fencing contractors. That novel was made memorable by the way they’d deal with someone they didn’t like: he’d find himself dead and buried head first under a fence post. The subtleties of drinking in country pubs were also explored: I still don’t know what the difference is between a straight edge and a curved edge pint glass, except that the glasses mark out class distinctions. The whole novel was completely mad.

He’s a strange one, is Mr Mills. He speaks to us from the perspective of someone transplanted into a rural working class environment, so in his first novel The Restraint of Beasts we joined an English fellow who had been put in charge of a pair of truly terrible Scottish fencing contractors. That novel was made memorable by the way they’d deal with someone they didn’t like: he’d find himself dead and buried head first under a fence post. The subtleties of drinking in country pubs were also explored: I still don’t know what the difference is between a straight edge and a curved edge pint glass, except that the glasses mark out class distinctions. The whole novel was completely mad.His second novel, All Quiet … is saner, taking on the ways in which a decent hard working individual will be exploited. What is remarkable about the novel is the complete absence of polemic: Mills simply tells the story of the nameless narrator, using a deadpan comic style with the occasional flourishes of more overt humour, such as when he is recounting the narrator’s efforts to obtain baked beans or nice biscuits from the local shopkeeper, Hodge. The humour is in the extreme measures needed in respect of such a trivial matter, and in the character of Hodge. Here is one attempt by the narrator to get some baked beans:

‘Baked beans, is it?’ he asked.The narrator claims to have had some history of working in some factory “down south”: they claim never to have heard of him. Apart from that, and the fact he’s picked up some skills along the way, we know nothing about him. Either working life has dehumanised him or he’s a stand in for us all. By contrast, pretty much everyone else in the community is both named and has their character deftly drawn.

‘You are open then, are you?’

‘Open every day,’ he said. ‘Early closing Wednesdays.’

‘Oh, I see. Right. Yes please, baked beans.’

He went to the appropriate shelf. ‘You’re lucky. These are the last two cans.’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘You’ll be getting some more in though, won’t you?’

Hodge smiled in a cheery way and clapped his hands together. ‘I’m afraid not.’

‘Why’s that?’ I asked.

‘No demand once the season’s over. Not worth opening another box.’

‘But I’ll be staying for a while now, so I’ll definitely be buying them.’

‘That’s what they all say.’

‘Who?’

‘People who come in here asking for things.’

‘You mean customers?’

‘Call them what you like,’ said Hodge. ‘There’ll be no more beans this year.’

He has decided to stay on for an extra week’s holiday after the end of the season at some lakeside North East England camping ground. His plan is to kick back and relax before taking off on an overland trip to India. Tommy, the owner, offers him a bit of work painting in exchange for a night’s free accommodation. Within weeks, he is in over his head – he ostensibly has a job repainting the seven rowing boats attached to the camping ground, but Tommy keeps interrupting with new tasks. As does Tommy’s 15 year old daughter (the only female in town) – she has him doing all of her homework (starting with an essay on “where I live”, just to indicate her lack of ability, or maybe it indicates her ability to manipulate). He’s also contracted out to cut firewood, to do sheepyard work and there is growing speculation that he’ll become the new milkman, as Deakin isn’t really up to it.

Meanwhile, he is amassing debts to be paid “all in good time” and afraid to raise the question of payment for his work with Tommy.

The one social outlet is to go to the pub. Again, pubs are used to draw vital social distinctions. He goes to the Packhorse, because it has the beer he likes. As he has stayed on beyond the tourist season, the locals are remarkably generous about welcoming him into their midst, shouting him, running a tab, getting him on the darts team. The losers go to the Ring of Bells. Our narrator is relegated there for a couple of weeks when he lets his darts team down. Here, there is no decent conversation to be had – not even from Hodge, with whom the narrator is still engaged in a cat and mouse game in order to be supplied with the biscuits he likes. He does get to go back to the Packhorse, but it is no longer the same: it is extremely hard for him to regain his position; made clear from the fact that he’s now only a reserve in the darts team. Within the Packhorse, too, we have a “top” bar created by having part of the pub two steps higher than the rest: this is where Tommy and a handful of the locals do their drinking, but our narrator never ventures there.

So, the greater part of the novel is simply tracing the narrator’s deepening involvement in the community. Sure enough, there’s a mysterious “accident” involving Deakin

With Mr Parker’s help I shoved the mooring weight over the edge. It plummeted into the depths followed by the long, rattling chain, and a moment later it was gone.The narrator’s assimilation is now complete: he takes over the milk round. But then in the final 20 pages, there is a denouement of sorts, something that has been hinted at since the beginning, with references to Tommy’s terrible temper every time the narrator errs, and to the completely useless Marco, who had worked for Tommy over the summer. Through careful control of text and character, we have been expecting an explosion from Tommy, ever since the narrator spilt green paint on his concrete driveway in chapter one. Although there is a bit of a tantrum towards the end, I think the point is that Tommy is never bad enough so that the narrator thinks “that’s it, sod you” (as he has earlier with Hodge). So, instead, things are actually worse: the narrator is basically stuck while less worthy people are getting the world trips (and the girl).

So was Deakin.

The Independent claimed Mills to be locating some sort of artistic space between Albert Camus and Enid Blyton(!). I’d suggest he has a more than passing connection with Flann O’Brien and a non-manic John Cleese. I also wonder if there’s a riff here on Stephen Dedalus’s “I will not serve”.

1 Comments:

To my mind this is Magnus Mills' best book so far. One literary journo has dubbed Mr Mills "the Kafka of the banal" and it seems to have stuck to the wall in the literary press - but I reckon his dialogue is more akin to Samuel Beckett than Franz Kafka.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home