Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles

This is the latest film from the very prolific mainland Chinese film-maker, Zhang Yimou, and quite a departure from his more recent works like House of Flying Daggers. I probably should have spent a little time reading about him before seeing the film, because I may have missed things, but it seems to me that this one was far more realistic, eschewing the highly symbolic and magical elements. No specific colours stuck out as carrying symbolic value and, unlike virtually all of his movies, there was no female hero. Nor is there any fighting at all. Instead, he seems to have given full reign to what one commentator has called the "son's gaze" but in a very conservative way.

After a ten year estrangement - we never really learn why but it seems to have been caused by the death of the mother - Takada learns that his son is very ill. (I think this is different as well - the central characters are Japanese.) Nonetheless, the son (Ken-ichi) refuses to see his father. Rie, the daughter in law, tells Takada that Ken-ichi has spent time in China, making a movie about a mask opera which celebrates one Lord Guan (who is the personification of loyalty), Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles, and has made many friends there. Dad gets it in his mind that to be reconciled with his son, he should go to Yunnan Province to meet his son's friends and to finish his work for him. He speaks no Chinese and in the small towns to which his mission takes him, he finds no-one who speaks Japanase. So, he has a translator - I'm not sure if it was an intentional joke, but it turns out that his translator is called lingo, and speaks about as much Japanese as I do:

Dad's mission turns out to be much more complicated that at first anticipated - his principal singer Li has been imprisoned, and won't be let out for three years. After recourse to his uselesss translator and another back in the city, he manages to get permission from the very obliging prison governor to film Li singing in prison. It turns out that Li is heart-broken because he has this 8 year old son back in his home village whom he has never seen but just learnt about. He can only perform once he's seen his son. So, off Takata goes to the Stone village - an actual town that sits on top of a huge rock about 110 km from the prison. The journey is more than a little trippy, with some amazing geology. Of course, the village elders are all happy to have the son go see his father, and they have a village dinner, in which the main street is set up as a very long dining table.

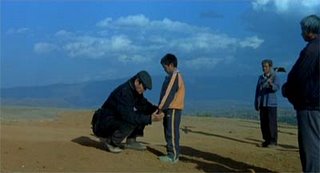

Dad's mission turns out to be much more complicated that at first anticipated - his principal singer Li has been imprisoned, and won't be let out for three years. After recourse to his uselesss translator and another back in the city, he manages to get permission from the very obliging prison governor to film Li singing in prison. It turns out that Li is heart-broken because he has this 8 year old son back in his home village whom he has never seen but just learnt about. He can only perform once he's seen his son. So, off Takata goes to the Stone village - an actual town that sits on top of a huge rock about 110 km from the prison. The journey is more than a little trippy, with some amazing geology. Of course, the village elders are all happy to have the son go see his father, and they have a village dinner, in which the main street is set up as a very long dining table.But it is here where the son's gaze idea becomes important, on at least a couple of levels. It turns out that Ken-ichi wasn't that popular here anyway, few even know who he is let alone admit to being his friends and Ken-ichi was only making the movie because it was something to do. Dad should scrap the idea and come home - but his conscience is so affected, and his idea of what he has to do to be loyal is so located in getting this movie done that he can't give up. It also transpires that Li's son doesn't want to meet his father - he runs away, leading to him and Takata getting lost in this area of rock formations:

- they'd be stalactites if they were in a cave, but they're not - just an area of very high and very pointy spikes of rock. They bond, and Takata wants the village to honour the boy's wishes as regards seeing his father:

- they'd be stalactites if they were in a cave, but they're not - just an area of very high and very pointy spikes of rock. They bond, and Takata wants the village to honour the boy's wishes as regards seeing his father:

I think there is something being said here about the old ways having to give way to the new and, indeed, that outside voices will have their part to play in sorting out the new.

Overall, it is a very gentle film, with a very strong sense of missed communications but with the possibility that if we work at it, we can get there - a lesson Takata is just now learning in relation to his son, when it really is too late.

1 Comments:

The whole Chinese film-makers telling Japanese stories--and the reverse--is interesting. Most of my students are unwilling to discuss this; the ethnic politics get them hot under the collar.

(I'm back writing at d-land; the hiatus, it turns out, was relatively short).

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home