The Memory of Running (Ron McLarty)

I'm in a state of shock: not only did the Warehouse have a range of suitable books, books that you just wouldn't find in your typical suburban bookshop, but they were all $5 each! I'm talking books like ClaireTomalin's Jane Austen: A Life and Samuel Pepys: An Unequalled Self. Books like Zoe Heller's Notes on a Scandal and Matt Ruff's Set the House in Order. Or there is the Penguin History of the 20th Century. Of course, I don't have the sort of family for whom any of these books would suffice as stocking filler, but since I like such things, I bought them all, and more.I mentioned that I was reading Nigel Cox's Responsibility: it turned out to be so good that before I had even finished, I rushed off to buy a copy for a colleague who left us for the north yesterday. Today, I became so enchanted with my current book, Sarah Hall's Electric Michelangelo, that I rushed off to buy a copy for another colleague as a Christmas present. These are brave moves given that the last person for whom I bought a book regarded it as such an impertinance that I do so that she has not spoken to me since. People are strange. We need more like Smithy Ide, the "hero" of the Memory of Running.

He is 43 and basically stopped functioning 20 years ago when his sister went missing. He has amassed an enormous weight (280 pounds - which gives him a BMI of 39 on a scale where 30 is obese) and works in quality control, ensuring that the arms of toy soldiers have been put on in the correct place - a far cry from the Vietnam war hero he was. As a young man, he would ride is Raleigh bicycle and run a lot, with plenty of warnings from his sister Bethany that if he ever stopped running, he'd become fat and worthless - pretty much where he has ended up. He is like his childhood pet, Malzone, who had to be fixed to prevent him from chasing after girl dogs - the vet says "He'll have a memory of running or something, and after a while he'll forget about the girl dogs and be fat and happy" except that Ide is not happy. Bethany's disappearance seems to have had the same effect on him as on Malzone: apart from three times in Vietnam where he paid for sex (before the respective women fled in horror, according to him) he has had nothing to do with women at all. The one woman he did ask out "laughed so hard her coffee came out her nose".

The novel starts with triple bad news for Ide: his father and mother are in a car accident and die in seperate hospitals, then he gets a letter to say that his long-missing sister, Bethany, has finally turned up: in a Californian morgue. He's in a bit of a daze, finds himself at his parents' house, where he notices his old Raleigh: ... I put up the kickstand with my heel and walked with the bike between my legs, to the end of the driveway. It must have been around eight, because I remember a full moon.

Now, I don't understand this, except I knew there was a Sunoco station at the bottom of our street, and it probably had an air pump, but, as I said, this is a gray area because all of a sudden I gave the Raleigh a few steps, sat ridiculously on the seat, and began to coast on the flat tyre rims of my bike, down our little hill.

And thus, without ever thinking about it, started his odyssey: he bikes from East Coast Providence New Jersey to Venice Beach, California.

Bethany is a tragic figure: she is apparently very beautiful, vivacious smart but at the same time, broken: she has a mental illness which causes her variously to take "poses" she can maintain for days, to disfigure herself quite hideously and to run away. This is another way in which Smith has a memory of running. There is nothing dodgy about his love for his sister, but it is clear he does, no matter how painful that might be at times: Another thing about love I remember. It's good and bad, but sometimes when you love somebody so much, you just can't forget how they are when they're hurt. When Bethany was hurt, when she cried and hit herself, it was kind of, I guess complete. All of her hurt. ... But I never saw things so complete as Bethany's sadness.

And then: You have to learn to look at someone you truly adore through eyes that really aren't your own. It's as if a person has to become another person altogether to be able to take a hard look. Good people protect the people they love, even if that means pretending that everything is okay. When the posing and the disappearing became a way of life for Bethany, we'd take on this almost casual approach in our searches.

Its a pretty straight-forward sort of philosophy but not a bad way of defining both good people and love.

Our story has four dimensions to it: the physical journey Smithy takes across the USA to reclaim the body of his sister, in which he comes across essentially good people; it was quite heartening - although he does manage to get knocked down by a truck, beaten up by a policeman and damn near killed by the son of his army buddy. There is the almost constant presence of his sister - she is either in his memory or a physical presence for him. There are his memories of his relationship with his parents and their shared love for baseball. And finally, there is Norma: she was Bethany's childhood friend who from the age of six loved Smithy - he was ten at that stage, so obviously didn't want some kid screaming out her love for him. But as he cycles his way across America, there is a growing connection between them.

I reckon this is a Pulitzer-worthy novel (the criteria is basically that it tell an American story) and yet McLarty had enormous trouble getting it published. I can't remember how Stephen King came to read the manuscript, but it was only when he did and told a publisher to publish it that this marvellous book saw the light of day.

Young Adam

I'm figuring that with Tilda Swinton playing in the Narnia movie, those theatres which are not showing it have been looking around to find other movies in which she has acted, so they have something for those who come out loving her as the White Witch. I can't see any other reason for the Metro showing Young Adam now: it came out in 2003. Ah well: any who do see it because of Narnia will be in for a small surprise if they see : its a deeply disturbing movie. Ewan McGregor is Joe: the film opens with him dragging a near naked young woman out of the Clyde river. This event has absolutely no apparent emotional impact on him at the time, surpising given that it is his former girlfriend, Cathie. As the movie progresses, he does start to show more interest - looking for news reports about it and then attending the trial of the man charged with her "murder". The style of the movie is to tell two parallel stories: the present one of the impact, or lack of it, of Cathie's death on Joe and the past one of the events leading up to her death. In his previous life, he was a struggling, frustrated writer who casually picked Cathie up at the beach one day and then lived off her. The story of their relationship is (deliberately) fractured, so we only get to see a few major events and have to draw our own conclusions. For example, there is a scene in which Adam (I think) rapes Cathie in a particularly degrading way - but it is possible that in the bits we don't see, they do engage in consensually rough sex. I think Cathie was crying as it happened, but am not really sure. Apparently, the captions say she is laughing: I do know that we see them quite composedly cuddled up together that night. Then, a while later, she kicks him out. We don't get to see what led to that. It is that which leads to his present life: he biffs his typewriter into the Clyde and is offered a job on a barge - one which mainly runs coal up these tiny canals from Glasgow. It is a very hemmed in life - there is Joe, Ella (Swinton), her husband Les (Peter Mullan) and their young boy. They live onboard, in a space about as big as the inside of Webster. The life they lead is not exactly spacious - most of the filming shows the barge surrounded by high banks, tunnels and locks with very few shots of open land or the sky. It is a part of the world I've never seen, nor expected to see in a movie: although oppressive, it had a kind of gloomy beauty and was wonderfully shot. Of course, the inevitable happens: since there are no other women in his life, Joe starts going after Ella (successfully). When Les catches them and leaves, Ella's sister moves on: she and Joe are at it that night. The audience knew exactly what to expect when Joe finally left the barge and meets this fellow in a pub who offers him lodging, saying that he works nights and so it would be just Joe and the missus a lot of the time. So, yes, there is lots and lots of sex - I've seen comments from a couple of reviewers that they had to leave because there was so much. It struck me as very strange sex - as inevitable and automatic as the barge trips, with a certain amount of physical tenderness but no emotional connection between anyone involved. And Joe's choice of women seem to get worse as he goes on: Cathie seemed to be truly lovely, Ella was a pretty tough nut and her sister was horrible: kind of like a slutty Hilda Ogden! But the true point of the story is the way in which Cathie came to die and Joe's failure to stand up and take any responsibility when he saw a man convicted of murdering her and being sentenced to death. Everything moves towards that moment.

"The Accidental" by Ali Smith

Sometimes bravery pays off. A while ago, I wrote of the trouble I had in getting into Hotel World but when Ali Smith's next book ws nominated for the Booker, I thought I'd try again. I'm so glad I did, although the end did turn out to be a bit of a fizzer. The Smart family is a fairly typical one from a particular societal niche: Michael is an academic, a teacher of literature. He has had a succession of sexual encounters with various of his students: at one point he brags to himself that his wall is covered by postcards from such students. He is extremely tacky but, nonetheless, has managed to get himself into a relationship with Eve (yes, her first husband was Adam). She publishes books of imaginary interviews with dead people and is a great success. She has 2 kids. There is 12 year old Astrid, who obsessively films the dawning of every day after seeing love letters from her father to Eve in which the image of the sun coming up every day became a symbol of fidelity. She also films signs of societal decay - such as the racist insults painted onto the Indian restaurant. There's a cute scene when she videos a surveillance camera for her "local researches and archives", much to the discomfort of the security guard who tries to stop her. Astrid Smart lives up to her name - her mind is a continuous whirl of word play and strange connections. Teenaged Magnus is stranger and very withdrawn: he and his mates had taken the headshot of one of their female classmates and superimposed it on a naked body before sending it around their school. This caused the girl to kill herself. They have come up to Norfolk on holiday. One day Amber just walks in to their lives: Eve thinks she is an unusually bold (and old, as she is in her 30's) example of the students she knows Michael is sleeping with. He thinks she is someone his wife is going to interview. Such is the gap between them that it takes several days for them to work out that no-one knows Amber - giving a nice irony to her proverbial "be careful not to let folk over your threshold till you're absolutely sure who they are". In the meantime, Michael has become completely besotted with her and Eve equally jealous and threatened. The reality is that Amber has bonded most closely with the kids: she spends hours wandering around with Astrid and, after saving Magnus from suicide, becomes everything his teenaged imagination might have imagined her to be in terms of a sexual partner. Poor Magnus: he's at dinner with the family and Amber is teasing him, causing him to blush at the memory of what they'd been up to and getting incredibly horny with it: his parents are all concerned that he's become sunburnt, which only makes things worse for him. So, for the kids, Amber is very much a positive influence whereas for their parents, she becomes a catalyst for the inevitable split between them. All of this is played out during the middle section of the book, which culminates in Michael expressing himself in bad sonnets before his text fractures completely and Eve interviewing herself (but passing on the hard questions) before giving Amber her marching orders when she comes home to find Amber fondling her son. The final section is a few months later: the Smart family gets home to find that their house has been stripped completely bare, right down to the doorknobs! The one thing left is the answering machine; it has some ominous messages which blow this already fragile family apart. There's a wonderful sequence in which Astrid is pondering her place in life at the beginning of the 21st century. She thinks of herself "hurtling through the air into it with a responsibility to heatseek all the disgustingness and the insanity, Asterid Smart the Smart Asteroid". But then: Hurtling sounds like a little hurt being, like earthling, like something aliens from another planet would land on earth and call human beings who have been a little bit hurt.

Take me to your leader, hurtling.

And Magnus is the hurtling - he is in real agony over his sense of responsibility for the death of his classmate, but has no-one to talk to; not, that is, until he finds his way to talking with his sister. I find myself crying again at the tenderness of that scene. The really good thing about this book is the way Smith chose to tell it. She had a formal beginning, middle and an end - within each of which she gave each member of the family their own chapter, told from their point of view and using their own distinctive voice. The one thing that didn't really work for me was that we see Eve, in her last section, walking into a house where she is mis-recognised, first, as the hired help and, second, as some esteemed guest. I had the strongest feeling that she had randomly walked in, looking for news of her father, and fallen into the same sort of opportunity Amber had seized.

A Cheap Shot

but someone had to take it. My colleagues were most impressed with it. A letter I found it necessary to write to the ODT, which they were kind enough to publish: I remain bemused by Ian Williams' review of The Fossil Pits (ODT, 3/12). He mounts a three-pronged attack - the first being that it needs a "ruthless editor", presumably because of the mid-paragraph jumps in narrative and the absence of speech marks [he complained about]. I suppose your reviewer would also have problems with other not so minor writers who employ the same techniques to a much greater extent - such as the Nobel prize winning author Jose Saramago or James Joyce.

A second objection is that the novel is "too clever" and lays down an "intellectual challenge" akin to giving readers the finger. Perhaps your reviewer simply is not up to the job; rather than accept it as a weakness on his own part, he blames the author. One simply cannot tell from the review but, I have to say, there can be no problem at all with authors who deploy their intellect to the fullest in their artistic endeavours.

The third criticism is most hard to understand: he complains that "serious" New Zealand writers are too complex! There appears to be an implicit assumption here that because he is a New Zealand author, Corballis should have eschewed complexity. Why?

Now I guess I should read the book. I did flick through it in the UBS and it did not strike me as being overly challenging. First, I have to finish reading Nigel Cox's Responsibility.

Little Fish

This movie is getting some very mixed reviews: Simon Morris raved, albeit briefly, about it on National Radio, saying it was a "grown up" movie; the Sunday Star Times was rather more subdued in its praise and another piece I read simply said it was "too slow". That, however, was its charm. This is a very textured film, one which is slow to put its cards on the table. I like that. Those familiar with the more pop of Australian cinema or with the underworld of drug-dealing might well expect something different: more cheese? singing? humour? more pace? a higher body count? violence? grit a foot deep? Romper Stomper it aint - in fact the movie it most reminds me of in terms of its developmental style is Japanese Story. Except for the bit where Hugo Weaving gives our Sam Neill a big old kiss fair square on the lips. A lot of the story is configured by events five years earlier: Lionel (Weaving) gets Tracy (Blanchett) hooked on heroin (the little fish of the title refer to Tracy's swimming habit and the little containers (apparently used in Asian restaurants for soy sauce, but we're obviously not that flash in Dunedin) in which heroin is trafficked as well as the place of the characters in the overall scheme of things), which causes Janelle (her mum, played by Noni Hazlehurst) to biff Lionel out on his ear. Tracy, her brother Ray (Martin Henderson) and her boyfriend Jonny (Dustin Nguyen) are all caught up in drug dealing until Jonny has a big car crash. His family spirit him away but Ray loses his leg and doesn't really seem to have done much in the intervening years. Tracy has managed to stay clean ever since: when we meet her, she's a manager of an Asian video shop in a suburban Sydney Mall, trying to find to make something of her life. She wants a bank loan so she can set up a net cafe and become the owner of where she works. She doesn't really think its enough, but can't think of what else she might want to do with her life. Of course, with her history, banks aren't exactly forthcoming. The film covers about a week of her life: the week in which she has committed to go ahead with setting up the net cafe but hasn't been able to tell anyone there is no money to do it with. It is also the week that Lionel is finally trying to go clean but only because his drug-dealing partnership with Brad (Sam Neill) has come to an end, meaning he'll have to pay for his drugs. He can't do it - he sends Tracy out to score for him, raising concerns with her family that she's going back into that scene. Tracy takes care of him simply because of all the men who came through her mother's life, and despite his hopelessness, Lionel was the only one who took the time to love them. And it is the week that Jonny comes back from Vietnam, keen on picking up where he left off with both Tracy and Ray. Ray is keen, but Tracy is much more reluctant. It is Jonny's return which gives the movie its forward movement - Jonny and Ray are plotting with Brad's former 2IC Steven (Joel Tobeck) to get some deals running. It turns out that Steven has been running deals his boss knew nothing about, which adds an extra dimension to the closing scenes. Then, when Tracy's thing with the bank doesn't pan out, it is Jonny who promises to work out a way to get the money for her. We know what that will be, but she doesn't, not for a while anyway. And so we come to a showdown, of sorts. The film finishes with Tracy swimming, and Ray and Jonny watching her. The Sunday Star Times criticised this as being too glib an ending, as if their problems are all behind them, but I don't know how they reach that conclusion. I'd say it is simply far too ambiguous an ending to know how things will be.

Rather than being a movie about events, it is really one about (a) the consequences of those events, (b) the need to take responsibility and (c) the relationships between the central characters. I have to say that almost everyone did a superb job: Cate Blanchett seemed born to the role and was stunning throughout. I did have a problem with Sam Neill, who didn't seem to take to his part too well, and was just Sam Neill. There was a cute quote from Martin Henderson during Simon Morris's review: he said he turned up to the set ready to go, found out how much work the other actors had done to get into their roles (Blanchett had interviewed drug addicts, for example) and felt shamed into doing more.

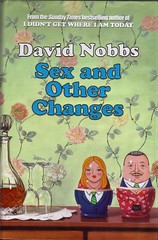

Sex and Other Changes

In the unlikely event that I ever put a foot into the dating scene, I think a useful litmus test sort of question is to ask about Reginald Perrin. Anyone who doesn't know who he is is too young. Plus, well, he had a particular sort of post-despair world view that had a lot of appeal, while managing to be hugely funny at the same time.His creator's latest effort has moved on, although there some familiar things, such as the pre-occupation with banally innacurate street names and hatred of stuffed shirts, represented here by bosses and the golf club captain. There were even a couple of echoes of Reggie's being late every day by exactly the same amount of time. Here, Nick and Alison are a lot more accepting of human frailty than our friend Reggie ever was. They would have to be, as it turns out they both need a fair amount of support from each other and their community. They meet as teens at the Thurmarsh Grammar School Bisexual Humanist Society, where Alison captivates him with her speech as to the possibility of unselfishness. There follows a fairly typical tale of school sweethearts and marriage, but 13 years in, Alison has a revelation in the menswear department of Marks and Spencer - she should really be a man.Before she can share this with Nick, he stammers through his own confession that he has decided to go through with sex re-assignment surgery himself. This leaves Alison in a strange place: she is so angry with him for stealing her thunder that she has to make life difficult for him, and thus can't tell him that's what she wants for herself. So, we have a nice situation of her doing the dutiful partner thing, as Nick goes through his counselling, his drugs etc while she says nothing.Not forever, however: once his change is a success, it is her turn. It is strange, but it is only when they have both swapped gender that living together becomes too awkward for them and they go off to find suitable partners.The book turned out to be a lot more subtle than I expected; rather than going for the funny bone all the time, there is quite a tender exploration of the tensions present in the relationship. Ultimately, he produces for us a classic romantic comedy, updated for modern conditions.