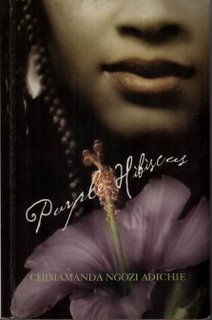

Purple Hibiscus by Chimananda Ngozi Adiche

One of my bookgroups is presently reading this: the general attitude is that it is an annoyingly slight piece of fiction, but I am not convinced. - I think there may be a little bit more going on with this novel than is apparent. First off, I think it is very much in a feminist tradition which sees a split between the public (male) and private or domestic (female) but which claims an equal importance for both. So, while there is a coup underway in Nigeria where some un-named Big Man has wrested control and is murdering his oponents, the concern with this novel is with the domestic consequences.

One of my bookgroups is presently reading this: the general attitude is that it is an annoyingly slight piece of fiction, but I am not convinced. - I think there may be a little bit more going on with this novel than is apparent. First off, I think it is very much in a feminist tradition which sees a split between the public (male) and private or domestic (female) but which claims an equal importance for both. So, while there is a coup underway in Nigeria where some un-named Big Man has wrested control and is murdering his oponents, the concern with this novel is with the domestic consequences.Furthemore, there is another, equally important, power struggle and coup being enacted secretly within the confines of the household, which is anticipated by the opening words of the novel

"Things started to fall apart at home when my brother, Jaja, did not go to communion and Papa flung his heavy missal across the room and broke the figurines..."Our narrator throughout is Kambali (15): she and her brother Jaja (who is either 14 or 17, I think there's a bit of a slip up) live with their parents, Eugene and Mama (a.k.a. Beatrice - she is hardly ever named, confirming the lack of any sort of public role for her). In some ways, Eugene is a good man, a very good man, even. He is a newspaper publisher and through his editorials and those of his editor, he stands up to the illegitimate government and the terrible things they do, he makes secret donations to a children's hospital and homes for orphans: the public perception of him is that he is a hero. Many are given strength by the stance he takes. To some extent, this continues through to his performance as a father: he is clearly very protective of his children, and wants the best for them. But there is a cost, and it is a terrible cost to pay: Mama is practically silenced by his repressive tyrannical ways and Kambali speaks only in a whisper and even then stutters.

There is a clue in Eugene's name to a critical tension in this novel: he has embraced the English ways, sees doing things the English way as the answer to Nigeria's problems, has turned his back on his native Igbo language and has embraced Catholicism to the point he refuses to have anything to do with his "heathen" father and won't let his children play unattended with their "heathen" cousins. So, when the kids err by spending unsupervised time with their grandfather, he pours boiling water on their feet. We learn of his tendencies early in the story - they have just been to Mass, Beatrice, heavily pregnant, is feeling sick and not up to taking tea with the young guest priest. Eugene asks, twice "Are you sure you want to stay in the car". Back home:

I was in my room after lunch, reading James chapter five because I would talk about the biblical roots of the anointing of the sick during family time, when I heard the sounds. Swift, heavy thuds on my parents' hand-carved bedroom door. I imagines the door had gotten stuck and Papa was trying to open it. If I imagined hard enough, then it would be true.Beatrice is not his only victim: Kambali is brought to the point that the final rites ("extreme unction") are administered and, let us just say that Jaja does not escape. Eugene apparently sees himself as doing god's work so that the devil does not win, can't understand why his family walk into and like sin. So, after one attack:

Papa crushed Jaja and me to his body. 'Did the belt hurt you? Did it break your skin?.. I felt a throbbing on my back, but I said no, that I was not hurt. It was the way Papa shook his head when he talked about liking sin, as if something weighed him down, something he could not throw off.Maybe it is this recognition that allows Kambali to maintain a steadfast love for her father, in the face of what most of us would regard as abuse. The author is quoted as saying that while his fundamentalism is definitely a problem, and symptomatic of a lot of what is happening in Nigeria:

for all of his fundamentalism, at least has a sense of social consciousness that is expansive and proactive and USEFUL, so while his character may be seen as a critique of fundamentalism, the God-fearing public in Nigeria can learn a bit from him as well.But there is another important element to this story. Kambali and Jaja are permitted to go and stay with Eugene's sister, ostensibly in order go on apligrimmage to see an apparition of the Blessed Virgin (there is a cute line about why she should be white and not appear in Africa, since she did come from the Middle East). We first meet Eugene's sister at the family Christmas celebrations:

Aunty Ifeoma came the next day, in the evening... Her laughter floated upstairs into the living room, where I sat reading. I had not heard it in two years, but I would know that cackling, hearty sound anywhere.Of course she would: this is the first laughter in the novel, possibly the only laughter she knows. Ifeoma is important: she is a woman who is not confined to a domestic role, she lectures at the University and, by her inhabiting that public role, we get to see quite a bit more of the consequences of the coup. Spending time with Ifeoma and her two kids proves to be a revelation for Kambali, who cannot understand a life not lived according to the strict schedules her father has set out for her. Two other people need special mention: Amaka is Kambali's counterpart, who has a lot of trouble sorting out her cousin - she misinterprets Kambali's disinterest in her music as disdain for the poor equipment upon which it was played, rather than a complete unfamiliarity with music, for example. It is only when Amaka leanrs more about Kambali's situation at home that the hostility dissipates: finally they are like sisters.

The other is the young and good looking Father Amadi - who creates feelings within Kambali she has never experienced before and doesn't really understand. He is possibly the most controversial figure, in that there are some who think he is not only interested in her as a woman, but encourages her - which is completely wrong for a Catholic priest. I'm not so sure: I think he recognises there is a fine line between making her feel silly for feeling something for him and him taking advantage of the situation, and don't think he ever does the latter. Certainly, he is a very positive influence upon her, encouraging her to develop her talent for running and to open up socially and three years later, they are still writing to each other with no hint of anything "lovey-dovey" in their letters, despite what others think.

The events of the novel are structured around Palm Sunday - which celebrates the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem on the Sunday before Easter. Most happened before Palm Sunday, which have culminated in Jaja's refusal to attend communion on Palm Sunday itself, and to Eugene's final meltdown. Somehow, Jaja's defiance is so bad that Eugene cannot even resort to violence against him just the breaking of the religious symbols. Then, well, I'd better not say any more about what happens at Easter.

Oh, the final point is that the purple hibiscus of the title is described in the novel as rare, fragrant with the undertones of freedom - a freedom to be, to do.

As for our author, she is the daugher of a former Vice Chancellor of the University of Nigeria, and just happened to live in the same house as had been occupied by Chinua Achebe (to whom the opening lines of her novel are a homage).

1 Comments:

I very much like the sound of this - the narratorial voice seems to have a lot to offer and I feel I should read as much work as possible coming out of Africa. :-)

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home