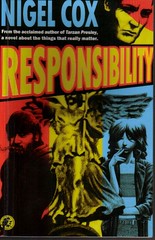

Responsibility

There is an interesting degree of correspondence between Nigel Cox (author of this novel) and Martin Rumsfield (the central character). For example, both grew up in Wellington, both moved to Berlin, both worked in project management and publicity for the Jewish Museum and, by the time you finish reading this novel, it seems inevitable that Rumsfield will be leaving soon. There's also a cute reference by Rumsfield to passing by the windows of Unity Books, where Cox worked.

I'd say that the essence of this novel is that Rumsfield is growing up (finally: he is 51!) and realising that others, such as his teenaged daughter, Sally, can be affected by his actions and that that should provide a guide for how he acts: hence the title. There is a vague hint at a feeling of responsibility for the holocaust as well, but this idea certainly is not developed.

That sounds serious, but the context for this morality is a pretty funny story, which gives the novel its momentum. When he was much younger, he had a mate, Shake (in some sort of weird homage to Shakin' Stevens - responsbile for such musical marvels as Green Door and This Ole House), who claimed to be a private investigator: he'd have Rumsfield follow various people about as his "Special Assistant" and so on. Nothing ever seemed to go right and really, Shake was probably just doing everything for his own amusement.

Of course, Shake turns up in Berlin: Rumsfeild is now married with children and doing his best as parent and father but Shake is a welcome diversion. He has a mad scheme: he thinks that behind the Nigerian letter scam, there really is a bunch of money and the key to wherever it might be is locked away in the Nigerian embassy in Berlin. He needs Rumsfield's help to break in. The promise of 100,000 Euros for a night's work is too great a temptation: it would, for a start, allow a return home.

This is where things turn a bit sour for our hero: Shake seems to have had a strange effect on the teenage daughter. She is also used in Shake's plan, to distract some guards; it is when she goes missing that night in Berlin, dressed as a hooker, that Rumsfeild feels his responsibilities quite keenly. There's a pretty tender scene when he rescues her from the predicament she has got into.

Just as well: earlier, it seemed that Rumsfield was taking a rather non-fatherly interest in his daughter:

Sally was also uninhibited, but in a different way. She undresses, in a bright pocket of sunlight, as slowly as possible... She has an immense towel, utterly white, and, standing on it, her skin is dramatically brown. She applies coconut oil, slowly, which adds to its lustre. She's naked, of course. Completely, and completely oblivious. Completely absorbed in the slow movement of her hands over her glowing skin, while she moves to some slow exotic music. Completely, utterly, entirely uninterested in whether every single eye in the area is focussed on her.Not so much, as it happens: Germans are apparently "grown up" about bodies and so pay little heed to such a spectacle. The person most interested seems to be her father - maybe the problem here is simply that he is employed as the narrator, but doing so leaves a funny taste about the nature of his observation of his daughter: not just here, but in other parts of the book.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home